A Culturally-Sensitive Chatbot

An NIH grant will help Weichao Yuwen and her collaborators adapt COCO, a caregivers' chatbot, to serve Latino communities.

(This story originally appeared on the UW School of Public Health blog as "Researchers at UW's Tacoma and Seattle campuses adapt AI-driven caregiver support tool for Latino community.")

Weichao Yuwen has heard many stories from caregivers about what it means to care for their chronically ill children, but there’s one story she’ll never forget.

In a study where her team asked caregivers to take a photo of their day, one person shared an image of a small window in their kitchen that looked out at a tree. The caregiver wrote that staring at the tree for a minute was the one moment they had for themselves because the rest of their day was spent caring for their child.

Yuwen, an associate professor in the School of Nursing & Healthcare Leadership at the University of Washington Tacoma, has been developing the program Caring for Caregivers Online (COCO) using health dialog systems (or “chatbots”) to serve the needs of the 50 million family caregivers in the U.S. who support people with chronic health conditions. Yuwen is now partnering with Assistant Professor Maggie Ramirez in the School of Public Health at the University of Washington in Seattle to culturally adapt COCO for Latino communities, whose morbidity and mortality rates and burden of childhood diseases are up to four times higher than for non-Hispanic whites.

Yuwen’s and Ramirez’s research partnership was recently awarded a $416,000 grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR), and has also been the recipient of several other grants, including from the UW’s Population Health Initiative and the UW CoMotion Innovation Gap Fund. The researchers will use community-based participatory research practices to adapt COCO and use innovative technology to assist the research process and fuel their chatbot that helps support the well-being of family caregivers.

“I want to jump in and take advantage of the new technologies that could have the potential to reach so many more people, but we’re trying to do this work more intentionally, where it’s about the people, not the technology,” Yuwen said. “As part of this grant, we want to establish or explore methods to use AI and machine learning to see if there’s any way to help us speed up that research process, but still in a very culturally sensitive way so that we do it right and not introduce bias into the language models.”

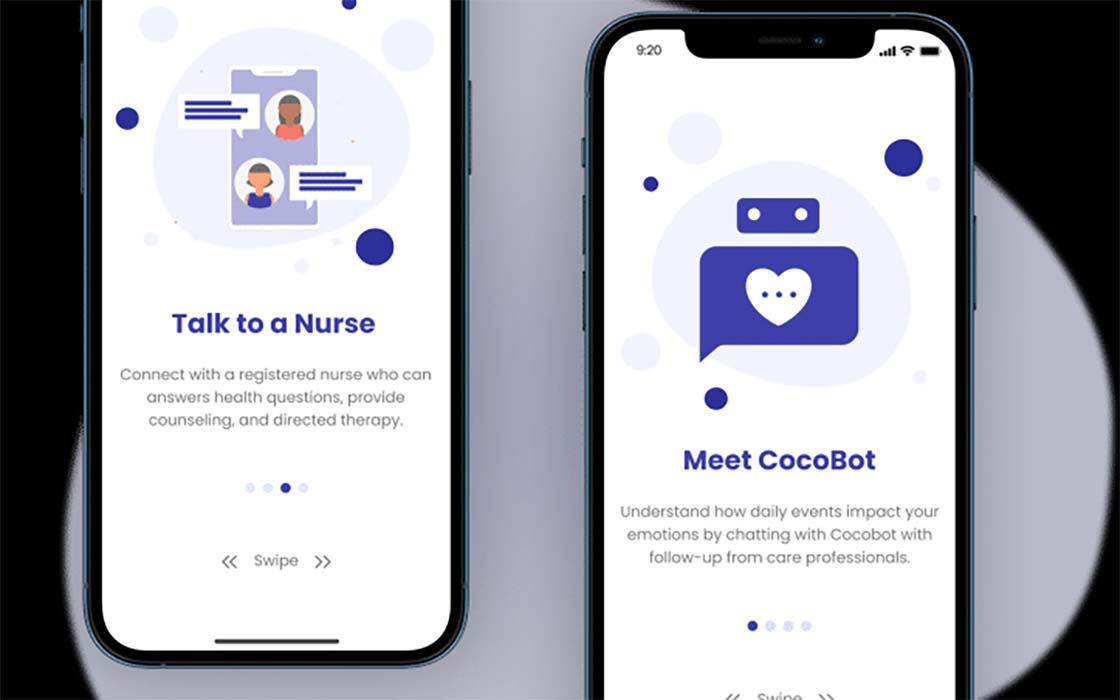

Caregivers for chronically ill children provide an estimated $100 billion in unpaid care services in the U.S. annually. This requires significant physical, mental and financial work on behalf of caregivers, which is where COCO can provide much-needed support. COCO, which is currently in its pilot stage, is a mobile-based chat platform that provides both automated dialogs and text-based interactions with healthcare providers including nurses. It can share tips for family caregivers such as understanding how events in the household impact a caregiver’s emotions, wellness practices for the caregiver and insight into how to care for their children.

Yuwen’s vision for COCO is to adapt the program to as many communities as possible, starting with the Latino community, which is the largest and fastest-growing minority group in the U.S. Latino communities are also more likely than other racial and ethnic groups to seek health information using mobile devices. After learning about Ramirez’s work adapting other evidence-based health programs for Latino communities, Yuwen and Ramirez decided to partner to expand COCO’s reach. Ramirez will work with community partners to understand how to best support family caregivers of children. These community partners include the UW Autism Center, the Puget Sound Asthma Coalition and Mujeres Latinas Apoyando la Comunidad, a group of Latina women who have been working in the South Sound since 2013 on issues such as asthma and childcare.

“It’s important to have the voices of the people who this work is intended to help at the table from the beginning so that it’s designed with their input, rather than us designing it in isolation from the end users,” Ramirez said.

The UW Autism Center has worked with Yuwen in the past on supporting caregivers through online platforms. Annette Estes, research professor and director of the center, said it’s critical for families who have children with autism to have access to online resources that can help them handle stress and receive training to support their children. Online tools mean caregivers can receive coaching without having to take time off from work, find child care, and find transportation into a center.

There are very limited resources available for parents and their children with autism, and wait lists for autism centers can be years-long, Estes said. Having easily accessible online tools like COCO allows parents to receive help far more quickly. The UW Autism Center’s Tacoma campus has many families who are low-income and non-English speaking, so connecting those families with COCO’s resources will be important for the study.

“It’s really exciting that Dr. Yuwen is bringing together this group of people who are looking at how to support caregivers that are in these different intersectional communities,” Estes said. “It’s very timely and I think it’s going to help a lot of people.”

Adapting programs for specific populations is about so much more than language translation, Ramirez said. In fact, translation is often the last step of adaptation. When Ramirez works with communities, she learns about their perspectives on health care or family.

For example, the word “burden” is often used by researchers or health care professionals to describe the work of caregivers for the people they care for. But as Ramirez has learned from her past research with Latino caregivers of people with dementia, “burden” can be an objectionable concept.

“I have found in my research with Latino families that the word ‘burden’ can be really off-putting because it goes against the cultural value of familism and the pride people take in caring for an ill or aging family member,” Ramirez said.

Knowledge like this can be used to help a platform like COCO communicate respectfully and accurately, so it can better support family caregivers’ needs. But this kind of close, collaborative work with communities can take years to accomplish. That’s why Yuwen’s and Ramirez’s research partnership will also explore how recent technological advances in AI can be useful for speeding up the research process, while not compromising the important work of close community partnerships.

Yuwen and Ramirez said the grants they received through the Population Health Initiative (PHI) helped them launch their partnership and earn funding from the NIH. The PHI grants supported them in studying how language models can help make health interventions more accessible and tailored to different cultures and languages. Yuwen and her team also received a grant to explore a Chinese version of COCO.

Ultimately, as COCO grows, Yuwen wants to make sure the platform supports rather than replaces human caregivers.

“Even for COCO, the purpose is never to replace human care. There are so many family caregivers that don't have any support right now or are not aware of the available resources for them,” Yuwen said. "We hope this work can reach culturally and linguistically marginalized communities through Latino COCO’s innovative, scalable, cost-effective, and high-impact approach.”