'To the Promised Land'

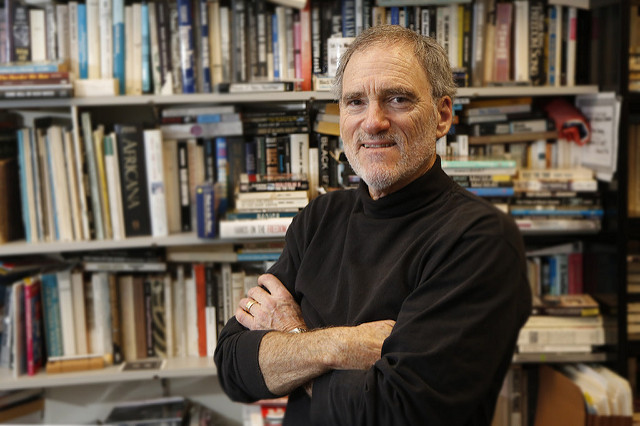

Dr. Martin Luther King's message of economic justice is the subject of a new book by UW Tacoma historian Michael Honey.

As the 50th anniversary approaches of the murder of civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, University of Washington historian Michael Honey reminds us in a new book that economic justice and labor rights were always part of King’s progressive message.

Honey holds the Fred and Dorothy Haley Endowed Professorship of Humanities at UW Tacoma, where he teaches African-American and labor history and Martin Luther King Studies. He has written five books, including “Going Down Jericho Road: The Memphis Sanitation Strike, Martin Luther King’s Last Campaign” (2007) and edited a book of King’s labor speeches, “All Labor Has Dignity“ (2011).

Honey’s new book, “To the Promised Land: Martin Luther King and the Fight for Economic Justice,” will be published by W.W. Norton on April 3 — the day before the 50-year anniversary of King’s assassination.

Honey sat down with UW News to discuss the book and the view of the slain civil rights leader that it reveals.

Is this a new view of King and his work?

M.H.: In some ways it’s not new, it’s been sidestepped when people talk or write about King. Most scholars of King know this material, but the general public does not, for the most part.

During the King holiday, mostly we hear that amazing speech, “I Have a Dream” of 1963. Students tend to think that King is endorsing the American system. Which is so far away from what King was actually saying and doing!

They become bored with it, particularly if they are upset about what they are experiencing as minority students, and/or as poor kids. They see King in a suit and tie, with perfect diction, seeming to talk about a colorblind society. But he was talking about it being 100 years since emancipation in 1963, yet millions of African Americans still live on a lonely island of poverty in the sea of an abundant society.

In this book, I put my emphasis on the roots of his family in slavery, so that the story starts with slavery. He was only the second generation removed from slavery, so his parents came from sharecropping and poverty. Due to the success of his father as a minister and King’s higher education, he escaped the cycle of racism and poverty that most black people suffered from, to become the person that most of us think of today.

Where does the book pick up the King chronology?

The story in “To the Promised Land” starts with his speech the night before he was killed. In Memphis, sanitation workers were on strike — in the midst of a huge crisis going on in that city. He was in the midst of trying to organize a poor people’s campaign to confront the federal government about racism, poverty and runaway militarism in 1968.

King had come out strongly against the Vietnam War one year to the day before his death. He wanted to channel the money that was going into the military into housing, health care, education, jobs — and sustainable incomes for all people.

What were King’s economic goals, his message?

He said in Memphis: “It’s a crime in a rich nation for people to receive starvation wages.” That remains a basic issue right now across the country, where it seems like the economy is doing really well but there are millions of people — about 40 million people — in poverty. There were 40 million people in poverty in 1968. And today there’s probably another one-third of the population always on the edge of falling into poverty.

Economically, things for poor people and working class people are probably worse in some ways now than in his time. The unionized, industrial jobs that created the black middle class in places like Memphis are mostly gone.

He came to Memphis to try to resolve that. One of the fundamental issues was: Do we make a way forward by paying cheap wages and keeping people without power on the job? King said the best anti-poverty program is a union. Where you can fight for your own agenda — somebody doesn’t have to hand it to you. But you have to be organized to do that. King always supported unions. He gave his life in that cause, in a sense.

Many workers in this country recognize King as a labor hero. “We can get more together than we can apart,” King said in Memphis. He always said we have a common destiny, and he put it in an economic framework. And we so need that.

What solutions did he suggest for economic justice?

His essential idea was a labor and civil rights coalition. And then he moved beyond that, to not only organizing for labor and civil rights, but organizing poor people. Rev. William Barberand others are trying today to replicate King’s campaign, and the Fight for $15, the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees — the union King fought for in Memphis — are trying to use the memory of King’s economic justice campaigns to move mountains again today.

King warned the AFL-CIO in 1961 that the right-wing business, military, corporate interests and racist interests in the south — the solid south, it was Democrats then now it’s Republicans — are forming a center-right coalition, and they’re going to take power. And that’s what’s happened. That is the Republican Party today.

His idea was that if you take the economic interests of poor people, Appalachian whites, Native Americans, African-Americans, Puerto Ricans, on down the line — and working class white people — you have a majority coalition. But for people to be able to do that they have to get clear in their own minds that that’s where their interests lie.

That we are better off together than isolated?

Right. And one must see that this right-wing coalition forming is not in your interests. One of the things that the coalition wants is the so-called “right-to-work” laws, which have spread all over the country. That’s a disaster for unions. King fought against them. “They provide no rights, and no work,” he said.

King put out red flags like crazy in the ‘60s. The way he looked at it, the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act in ‘64 and ‘65 were just the opening to a larger freedom movement for the American people. He called that Phase One of the Freedom Movement. Phase Two is what he called in Memphis, “economic equality.”

He said economic equality doesn’t mean that we all make the same wages or that we are all in the same class. It means that everybody has an equal chance to live a good life. That means education, health care, jobs, housing — all the basic things that everybody should have. He said in the richest country in the world there’s no reason we can’t do that and eliminate dire poverty.

People would say, “Well it costs too much.” Yet how many trillions of dollars do we spend on these forever wars? How many trillions do we spend on bank bailouts and corporate bailouts? You could have done away with poverty in the world, probably, if you used that money differently.

And that’s what he was saying then. His last book was “Where Do We Go From Here? Chaos or Community?”He said these are your choices. Lots of people are aware of all of this. But, it’s good to bring it into focus, and that’s what I hope this book will do.

Honoring Dr. King at UW Tacoma

50 Years Since King: We Remember.

On Wednesday, April 4, 2018, students, faculty, staff and the community are invited to campus to participate in a ceremony marking the 50th anniversary of Dr. King's assassination at the Lorraine Motel.

This event is part of a larger Day of Remembrance planned by the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, Tennessee. The day culminates with a moment of reflection at exactly 6:01 Central Daylight Time. Concurrently, a bell will be rung 39 times — one for each year of Dr. King's life. Just as news of King's death was first known in Memphis and then rippled throughout the country and across the globe, the first bell chimes will begin at NCRM and the King Center at 6:01 p.m., with local, national, and international chimes to follow. People wanting to participate in the campus ceremony should gather at the flag pole near the bottom of the Grand Staircase at 3:45 p.m. The bell ringing on our campus begins at 4:05 p.m.

What got this project started?

The last big book I wrote on King was called “Going Down Jericho Road,” a 500-word tome about King’s last campaign and the Memphis sanitation strike. It won the Robert F. Kennedy and other book awards. But I thought we needed something more readily accessible to students and to people who aren’t historians. “To the Promised Land” provides an opportunity to look back and reassess and rethink. Every chapter is framed around an idea and a quote from King — so it looks at King through what he was doing and what he was saying. It’s not a biography — other people have written fabulous biographies of King, and it’s not that.

What would the world be like if the economic justice that King preached all came true? What would be the working parts of such an economic reality?

The Poor People’s Campaign said everybody should have health care, everybody should have a median level of income — not poverty income, a median level of income, such that you can live a normal life. And education, and housing, and jobs at union wages. King thought the role of government is to bring about social justice.

To those who say it’s not the government’s job, King would ask, Well, what is the job of government? Just to benefit the rich?

Was he saying the government should provide income as a sort of entitlement program?

I wouldn’t put it that way. First, he was a social critic. He said if you don’t know what the ills are, you can’t come up with a cure. Second, he said, these are the things that people need. These are the assets we have as a country. We can solve these problems — but I’m not the government. I’m not the politicians — you guys have to figure that out.

If jobs are disappearing because of mechanization or offshoring to other countries you don’t just leave people shackled in poverty. Most other wealthy countries don’t do that. People talking today about an alternative minimum income tax. It’s not a welfare program, it’s based on the tax structure.

Finally — and maybe it’s not fair to ask — but what might King have made of our chaotic times?

He’d be disgusted, at the least. He would say the Trump and Republican agenda is obscene. It takes the right wing threat beyond what he expected, although he also wrote in 1968 that he feared racism would lead to an American form of fascism.

He also said, extreme poverty is like cannibalism — it’s something that once existed that should never exist again.