Hacking Their Way to Cleaner Water

UW Tacoma’s Clean Water Challenge 2014 brings together community partners and problem solvers to tackle local environmental questions.

Is it possible to tell if your water is safe to drink just by photographing it with your smartphone?

Can we develop an efficient route to clean out debris caught in storm water basins around Western Washington?

How do even small changes in air temperature and precipitation impact our water supply? Can we predict and visualize these? Could that information help us resolve water rights issues?

These and other use-inspired research questions were studied by diverse teams of problem solvers at the Clean Water Challenge, a full day of collaboration hosted by UW Tacoma’s Center for Data Science.

The event on July 12 brought together environmental scientists, civil engineers, geospatial researchers, data scientists, app developers and database engineers to focus on clean water issues. Faculty, students and community partners all worked together to tackle challenges related to water quality and resources. Fueled by coffee, pizza, and passion for solving difficult problems, teams spent the day gathering data, developing plans, building web apps and presenting their results.

What’s a Hackathon?

The Clean Water Challenge was modeled after popular “hackathons” held in the startup world. Hackathons bring together software developers, computer programmers, project managers, and others to create a new project in a short time period – from one day to a week.

Like other hackathons, the Clean Water Challenge sought to tackle real-world problems. However, the Clean Water Challenge was rare in its focus: bringing technology to bear on ecological problems. As Blair Deaver, software product manager for Geoengineers and a hackathon veteran, points out, it’s “pretty rare to have a science and technology event like this.” Most hackathons look at civic issues, rather than environmental ones.

Tackling Tacoma’s Questions

By bringing technological knowledge to environmental questions, the teams were able to investigate a variety of topics, tied by common themes. David Hazel, Managing Director of the Center for Data Science, says, “The two main threads [were] availability of water resources and the quality of the water.”

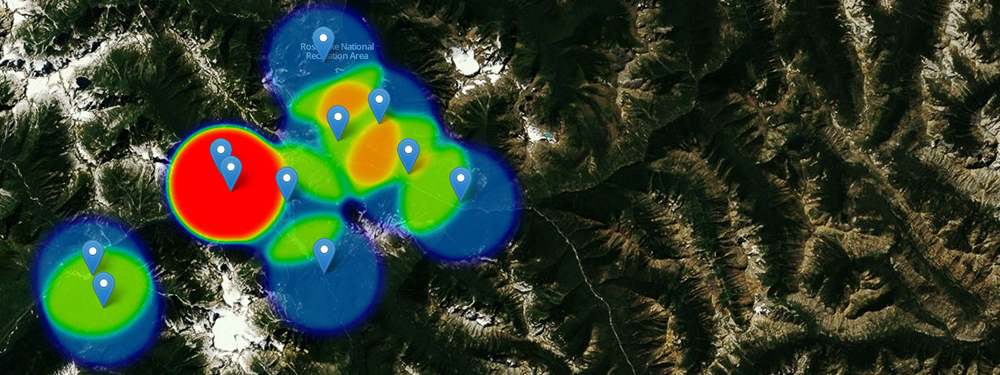

One team looked at water supply, focusing on Pacific Northwest mountain snowpack. They sought to visualize what a few degrees of air temperature change would mean for the area’s water supply. On the day of the challenge, the team was able to create a “proof of concept” app to visualize snowpack, which produced the image above. However, due to the time restrictions of the challenge, the image above was produced with “synthetic data.” One potential next step would be integrating temporal USDA Snow Telemetry (SNOTEL) data, USGS stream gage data, as well as NOAA historical weather data, to build models which show relationships between the data sets.

While one group keyed in on better-understanding the source of Tacoma’s water supply, another focused on its response to storm water runoff. Basins throughout our region process rainwater, removing pollution and contaminants like motor oil and cigarette butts. These basins continuously fill with debris and must be cleaned and serviced regularly to work properly.

But the basins fill at different rates; the maintenance trucks have different fuel efficiency, depending on the amount of debris they’ve picked up; and the distance between basins varies. While traditionally, computer scientists have strategies to solve routing problems (like the classic “traveling salesman problem”), this case integrated factors best understood from a variety of disciplines. One group at the Clean Water Challenge took advantage of the variety of skills in the room and tried to find the most efficient route, taking all these variables into account.

“It ended up being this really interesting problem that, on the face of it, looked fairly straightforward,” says Hazel.

Ideas for Clean Water Challenge projects came directly from Tacoma, as the event centered on use-inspired research. The problem of storm water debris collection came directly from a local business owner, who deals with routing questions daily. Tracking snowpack in the mountains was suggested by event sponsor Geoengineers’ current research.

A Meeting of the Minds

One of the core elements of a hackathon is that it brings together groups and individuals with different areas of expertise. Participants in the Clean Water Challenge had backgrounds in the environmental sciences and environmental studies, urban planning or geospatial analysis, law, marketing, design, and of course, computer programming.

Events like these, Hazel says, are about “raising awareness and getting people who normally wouldn’t think about these things to shift their focus” and apply their knowledge.

In one case, a student majoring in environmental studies was passionate about mitigating the water contamination caused by discarded cigarette butts. She attended the Clean Water Challenge in search of new perspectives on how to target cleanup.

The Clean Water Challenge also brought several local businesses to the UW Tacoma campus. The Center for Data Science partnered with local and national businesses Geoengineers, 2bridges Technologies, Microsoft Azure for Research, and esri, which brought resources, skills and people to the event, as many employees participated. Some Geoengineers and esri employees focused on gathering data sets for the teams to use, while Microsoft Azure for Research provided technological infrastructure.

Expertise also varied greatly among participants, who ranged from CEOs to third- and fourth-year students. Deaver recounts working with a student on his team, saying, “She began to start seeing the steps and the skills that we’re using [in this field] and how those map back to what she’s studying and learning.”

The hackathon gave students real-world experience working with professionals. “It’s those types of experiences that make the transition to industry that much easier,” says Hazel.

It may also have helped some get jobs after graduation. Deaver says hackathons are “a great place to work with and find passionate potential employees.”

Looking Ahead

Because the challenge was limited to one day, much of what came of it were threads and lines of future investigation, ones that might end up as graduate student projects. The event also helped build community ties between UW Tacoma and local businesses, helping connect the work done at the university to the larger community.

“We see Tacoma playing a part in the future of the technology landscape, not just as place to gain skills,” says Chris Anderson, CEO of 2bridges Technologies, one of the event sponsors. Anderson and his wife also participated in the Clean Water Challenge. The Clean Water Challenge helped apply UW Tacoma research and knowledge to the region’s problems, and connect students to the tech industry in the area.

Anderson adds, “I am so thankful for University of Washington Tacoma’s influence in my hometown, and it gives a real future to our city and a hope that we will originate our own business and talent.”