An Organized Life

Mike Honey, a founding faculty member of UW Tacoma, may be retiring, but he will continue building on his legacy of 'telling the story, telling history, telling reality.'

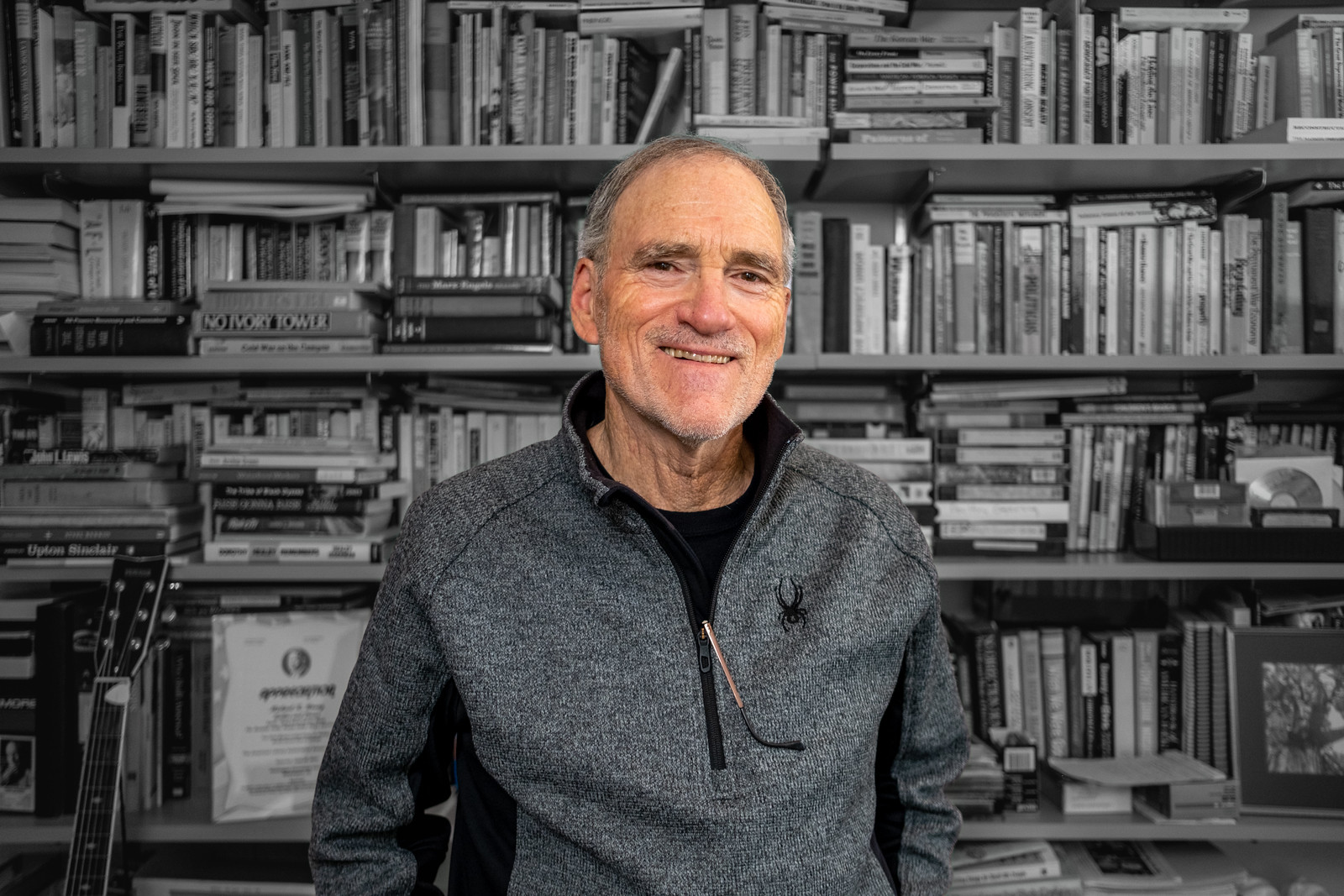

In this episode of Paw'd Defiance, the UW Tacoma podcast, we tour Mike Honey's office. Filled with books, posters, memorabilia, guitars, records, cassettes and research materials, the office has been his home on campus since 1997.

Thick plumes of black smoke roll into Mike Honey’s jail cell. The smoke is from a fire intentionally set by some of Honey’s fellow inmates. The 21-year-old has been in the Munfordville, Kentucky, jail on charges of jury tampering for three weeks. “I was never out of this four by seven cell, couldn’t shower,” said Honey. “I had some light coming in through the bars and could talk to people in other cells. It wasn’t total isolation, but it was pretty bad.”

Honey scrambles to the floor and wraps his coat around his nose. “I was coughing and having difficulty breathing,” he said. The jail is alive with the sound of men alternatively calling for help and gasping for air. Minutes pass before a jailer finally arrives in the corridor outside the bank of cells. “He lets everybody out but he leaves me in there because I’m the real dangerous one,” said Honey.

Honey and his then-partner Martha Allen came to Munfordville in the spring of 1970 as co-organizers of what they called an “anti-repression project.” Honey worked for the Southern Conference Educational Fund, an organization that promoted social justice, civil rights and peace. Honey and Allen put together a pamphlet about the “Black Six” case and distributed it all over town.

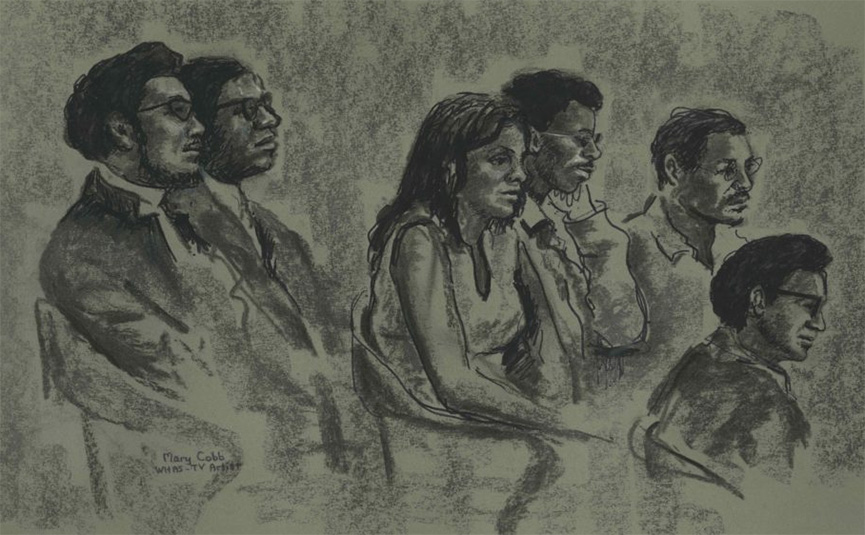

A little context about the “Black Six” case: protests erupted all over the country in the wake of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr’s assassination in April of 1968. “In Louisville, post-King, they had a rally in the Black community and the police came and started pushing people around,” said Honey. “The next thing you know, it turned into a riot. When it was all over, prosecutors charged six leaders of the local Black community.”

The letter and flyer Honey and Allen mailed to every listing in the Munfordville phone book urged residents to protest the trial.

The trial had been moved from Louisville to the sleepy town of 1,200 because, as Honey put it, “The prosecution said, well, we can’t get a fair trial in Louisville because nobody believes they’re guilty. What we didn’t know is that the judge in the case ruled that we were trying to influence the jury, even though no jury had actually been convened yet,” said Honey.

The judge issued an arrest warrant. “I was home by myself in our Louisville apartment and it must have been something like eight in the morning when I get a knock at the door,” he said. “They were plainclothes Louisville police. They came in and arrested me, they went through our apartment, took photographs from our wedding, took my diaries and our correspondence as evidence.”

Allen had been in Washington, D.C., working on another anti-repression project. When she returned to Louisville, she was arrested.

Both Honey and Allen found themselves back in Munfordville, booked into the local jail.

And then the fire.

The jailer eventually returned and let Honey out of his cell. He was safe from the flames but that doesn’t mean he was out of danger. He was a white civil rights activist advocating for the release of five Black men and one Black woman during a time of unease and tension in a South wrestling with the end of Jim Crow.

It was Honey’s and Allen’s first time in jail. “It served as a great education in how the criminal justice system does not work for poor people,” said Honey. “At that moment I thought, ‘Who am I, what am I doing here?’ I was in shock, I mean, I was a privileged kid and had never experienced anything like this.”

A Tumultuous Time

Born in April 1947, Michael Honey grew up during a tumultuous time in American history. The fragile alliance forged between the United States and the Soviet Union during World War II collapsed, ushering in the start of the Cold War. This period in the U.S. is marked by concern over nuclear annihilation and Communism. “The Red Scare was well underway by the time I was born,” said Honey. “You could be incarcerated for belonging to the Communist Party. It was just a ferocious period of oppression of civil liberties.”

“I think the key to me is actually my parents.”

——Mike Honey

Honey is the second of three children. “My parents came from working class backgrounds in Detroit,” he said. “My mother was raised as a Catholic and my father was raised as a Christian Scientist.”

There’s a telling anecdote from when Keith Honey and Betty Miner, Mike Honey’s parents, tried to get married. It’s 1943 and Keith has just returned to Detroit from fighting in South Pacific as a member of the Navy. “A plane he was on crashed and he nearly died in the war,” said his son, Mike.

Keith and Betty had been together since high school when they made the decision to get married. “The Catholic Church insisted that my dad had to convert in order to marry my mother,” said Mike Honey. “He agreed to that, but then the Church told my parents that their children would have to be raised Catholic and my dad said ‘Well, I’m not doing that. That’s up to the children.’”

The couple eventually married and raised their children as Unitarians. “They wanted a church that gave them an open framework,” said Mike Honey. “My parents firmly believed that children have the right to make their own decisions and to think for themselves.”

Mike Honey describes his family as middle-class. His father started out working in a factory. With the tuition benefit from the GI Bill, he became the first person in his family to get a college education. He became an urban planner before becoming a professor at Michigan State University. His mother took care of the home and was active in different organizations including the Unitarian Church, the Democratic Party and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom.

There’s this picture of a teenage Mike Honey — crew cut, clean shaven, wearing a suit — that fits into the stereotype of an “All-American boy.” This might be the image, but it’s not the whole picture. Beneath the squeaky-clean image on glossy paper is a “radical” in the making.

Honey spent his teenager years in a majority-white town, Williamston, Michigan, just outside of East Lansing. This was the mid-1960s and the civil rights movement was in high gear. The Honeys had family in Detroit and Mike went along on regular visits to the city. “Detroit was a hotbed of the Black Freedom struggle,” said Honey. “We [Honey and his family] were conscious of not only civil rights, but the economic rights and struggles of African Americans.”

Martin Luther King, Jr., is widely revered today by people from a diverse range of backgrounds. This wasn’t the case for most of King’s life as an activist. Many white people of the time disapproved of King. It’s a testament to Mike Honey’s parents that they let their son reach his own conclusions. “I started listening to King on the radio and watching him on TV, and reading his books,” said Honey.

Honey was athletic in high school, but also played guitar and sang folk music with a student group called the Williamston Wayfarers. His music soon took on the political overtones of folklorist Pete Seeger, and Black musicians like Odetta.

Honey graduated from high school in 1965. The 18-year-old had to register for the military draft shortly after his birthday. “I was reading King’s works on non-violence,” said Honey. “Around that time King was telling people they should become conscientious objectors, that they shouldn’t fight in the war. So, that’s what I did. I filed the paperwork to be a conscientious objector and that changed everything, really for the rest of my life.”

College Crusader

Honey didn’t go to Vietnam. Instead, he got a deferment to study history at Oakland University (OU) just outside of Detroit. “At the time, the campus was almost completely white in terms of students, faculty and staff,” said Honey. Even so, OU is where the Mike Honey of today started to take shape. He joined the school newspaper and worked his way up until he became the paper’s editor. “We turned it into a crusading newspaper on civil rights, the war and the feminist movement,” he said.

Honey started a chapter of the Students for a Democratic Society at Oakland University. During his sophomore year he organized a fast against the Vietnam War. “The FBI picked that up,” he said. “They came down to my campus and started asking around about me.” Nothing happened to Honey, however the FBI did open a file on him that would eventually swell to more than 800 pages.

MLK’s words and dedication to a just cause lit a spark in Honey. King’s assassination in April of 1968 could have been the reverse: it could have extinguished the flame now burning in Honey, but it didn’t. Honey and Allen attended the Poor People’s Campaign in the summer after King’s Death. A year later he participated in a peace march, the Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam, in the nation’s capital.

Honey and Allen graduated from Oakland University in 1969 and not long after Honey received a notification that he had been drafted. “I’d been sending things to the draft board for four years that I was a conscientious objector,” he said. “I had letters from my parents and my professors, and even the chancellor of my university, saying ‘This person shouldn’t be put in prison, he’s a genuine conscientious objector.’”

The draft board awarded Honey objector status. “When you’re a conscientious objector you have to do alternative service to the military for two years and so I got a job with the Southern Conference Educational Fund in Louisville, Kentucky,” he said.

Mike Honey and Music

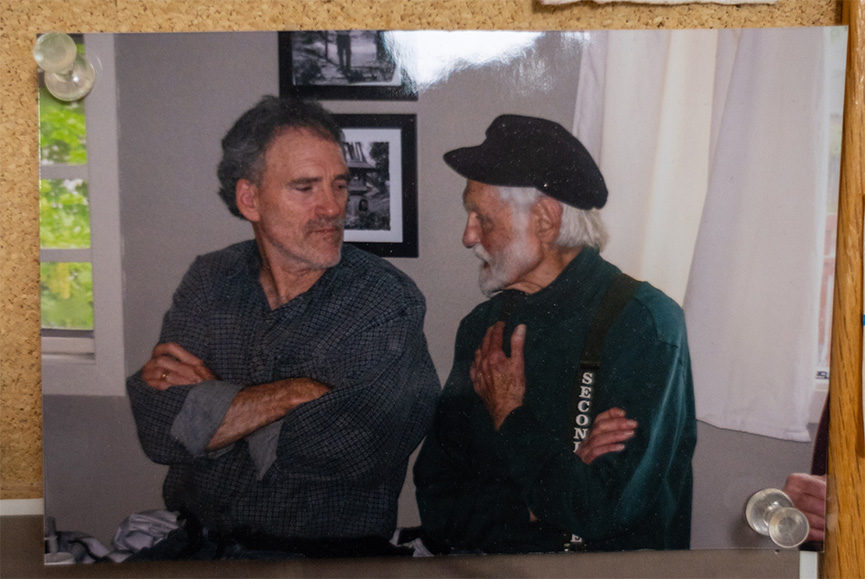

John Handcox, left, and Mike Honey

Mike Honey, left, and Pete Seeger

FIrst photo above: Singer, poet and labor organizer John Handcox, left, with Mike Honey on guitar. In 2013, Honey published "Sharecropper's Troubadour: John L. Handcox, the Southern Tenant Farmers' Union and the African American song tradition". Photo courtesy Smithsonian Institution Folkways Recordings.

Second photo above: Pinned to a bulletin board in Mike Honey's office is this photo of Mike Honey and famed folk singer Pete Seeger. Honey first met Seeger in the 1970s. Seeger provided a forward to Honey's history of labor organizer John L. Handcox.

Mike Honey never thought he would be an educator. At one point he considered becoming a professional musician. An older cousin taught Honey how to play the guitar. “I started playing music with him, and he was in Detroit, and he liked this kind of honky tonk music,” said Honey. The budding musician developed an interest in folk music that is still with him today. “Most of those songs are story based,” he said. “So, just by listening to this music you could learn history.” Honey’s skill with the guitar turned into a powerful teaching tool. He regularly brings his guitar to class and play songs that were part of the labor and/or Civil Rights movements. “Students usually like it if you throw something in there that’s different,” he said. You can hear Honey play here.

“He’s a Communist”

As Honey describes it, the entire town of Munfordville came out to watch the fire. The jailer shepherded the inmates outside the building. This same jailer had spent the past three weeks threatening Honey and trying to turn the other inmates against him. “The jailer told them ‘He’s a communist, you do what you want with him,’ but none of those guys gave a s**t about any of that.”

Prosecutors eventually dropped the charges against Honey and Allen. The “Black Six” case was ultimately dismissed. At this point in his life, Honey could have chosen to go another — perhaps safer — route, one that didn’t draw the attention of the FBI or didn’t result in him being threatened with arrest, or worse.

He didn’t.

Instead, Honey took a job as Southern director of the National Committee Against Repressive Legislation, and he and Allen moved to Memphis to set up an office. “We went from the frying pan into the fire,” said Honey. “We did that because Memphis was one of the capitals of police brutality in the South, and we thought we could do something about it.”

Honey spent the next six years traveling around the South. “I set up committees in different states with the goal of getting people to write to their representatives to block these Nixon-era repressive laws,” he said.

Honey and Allen were also very active in the campaign to free Angela Davis. The activist faculty member at UCLA and open Communist Party member spent a year in jail on murder charges before being acquitted. “We could see a frameup coming for Angela and many other anti-war and Black activists and feminists,” said Honey. He and Allen organized campaigns in the South to, as he put it, “free all political prisoners.”

He didn’t have a law degree, but that didn’t stop Honey from investigating cases of police brutality on his own. Through this work Honey developed friendships with members of the local Black Panther Party. “One time the police had surrounded the Party headquarters and they [members of the Black Panthers] called me, they needed some help,” said Honey. “So, I put on a jacket and tie. I went down there and sat on their porch. Finally, the police went away. They didn’t want any white witnesses.”

“Our phones were tapped, our pictures were constantly taken, and the FBI and the Red Squad [a Memphis Police secret intelligence unit] followed us and others active in the movement. We knew it, and tried to ignore it,” said Honey.

Honey’s decision to insert himself into tense situations shouldn’t be seen as the hero riding in to save the day. This is true of all of Honey’s work when it comes to issues of civil rights. “I’m there helping to make something happen or to tell about what happened,” he said. “I’ve done a lot, but I don’t take credit for any movements. I’m just somebody who’s helping it along. It’s other people who paid a heavy price.”

By 1976 Honey had reached a point of exhaustion. “I also thought I needed to understand things much better than I did,” he said. Honey made the decision to return to school. He and Allen both applied to, and were ultimately admitted into, Howard University. “We were both offered full scholarships,” said Honey. “We couldn’t have gone to graduate school without that money and encouragement from Howard.”

Founded in 1867, Howard University is one of 107 historically Black higher education institutions in the United States. “It was a great place to go if you wanted to be immersed in the Black experience and Black studies,” said Honey. “A lot of civil rights think tanks were at Howard in the thirties and forties which influenced what we think of as the Civil Rights Movement that came later. The faculty and students, many from Africa and the Caribbean and almost all of them Black, welcomed us. From there on I knew what I wanted to do.”

What Honey wanted to do was study history, particularly the histories of civil rights and labor and the intersection where those two meet. Honey completed his master’s degree in history at Howard and would later earn a Ph.D. in the subject from Northern Illinois University. “I was educated at Howard and Northern Illinois by experts in labor and African American history,” he said.

Coming to UW Tacoma

Honey completed his doctorate in 1988. By then, he and Allen, who have remained close friends to this day, decided to go their separate ways.

Honey met Pat Krueger at the University of Puget Sound in Tacoma. Krueger was a professor in the university’s music education department and Honey worked as a visiting faculty member at UPS for a year. Honey went to Stanford University on a fellowship, and he and Krueger got married.

Honey calls what happens next a “fluke.” He’d heard murmurings about a planned Tacoma campus of the University of Washington but didn’t know the details. Honey’s experience is a testament to happenstance and how being in the right place at the right time can change a life. “I was at a history convention and bumped into a friend who asked if I’d seen the job ad for UWT, which I hadn’t.”

The budding scholar found the ad but there was a problem. “The date to apply had already passed,” said Honey. Still, he took a chance and sent in his CV. Honey got a call a little while later asking him to come in for an interview and to give a talk about a subject of his choosing. “My talk was called ‘Links on the Chain, Labor and Civil Rights Through Music’,” he said. “I pulled out my guitar and I sang my way into UWT.” It helped that Honey had already been publishing articles in scholarly journals and had started building a reputation in his field.

“Campus” at that time consisted of a few rooms inside the Perkins Building in downtown Tacoma. “We only had 12 faculty when we started plus one director,” said Honey. “So, you kind of had to be able to do almost anything.” UW Tacoma didn’t have much back then, but it did have a mission, one focused on providing access to higher education to individuals while working to revitalize both a city and a region. “I really wanted to be in Tacoma, and not just because Pat taught here,” said Honey. “It reminded me of Memphis, very diverse, very working class, full of urban problems but also great people. I just felt like my mission was here.”

Scholar and Educator

Mike Honey’s growth as a scholar and educator coincided with the campus’s growth as an institution. During his 32 years at UW Tacoma, Honey has helped shape or create countless classes, programs and initiatives on campus. You can find Honey’s influence in the classroom through courses like “Labor and Community Organizing: Doing Community and Oral History,” “Life and Thought of Martin Luther King, Malcom X and Angela Davis,” “Black Labor in America,” and “The Black Freedom Movement in Perspective.” His focus on oral history brought about the creation of the Tacoma Community History Project, an important archive capturing the voices of many community leaders.

The fact that there is a School of Nursing & Healthcare Leadership or a School of Interdisciplinary Arts & Sciences or an Ethnic, Gender and Labor Studies degree is due, at least in part, to Honey’s work with different campus committees. Most recently Honey helped organize and launch the Labor Solidarity Project, which “highlights labor studies in the curriculum, in research, and through community outreach.”

It’s hard to overstate Honey’s legacy at UW Tacoma just as it is hard to overstate his impact as a scholar and educator. Just touching on some of the highlights:

- Honey recently completed a year-long fellowship with Harvard University’s Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, one of a small group of institutions, including the Institute of Advanced Studies in Princeton, N.J., that foster advanced research and intellectual exchange.

- In 2011, he was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship.

- Also in 2011, he was named a UW Simpson Center for the Humanities Society of Scholars Fellow.

- Honey has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities (1989 and 2004) and the Stanford Humanities Center (1989).

- From 2000 to 2004 he chaired the UW’s Harry Bridges Center for Labor Studies.

Honey published his first book, “Southern Labor and Black Civil Rights: Organizing Memphis Workers” in 1993. The book won three awards and set in motion a cycle where Honey would receive a fellowship giving him time to research and write a book that would win awards, which would open up more avenues and further fellowships. “I’ve had periods of time where I could just intensely do scholarship, and that is not normal,” he said. “I’ve been really fortunate, and it’s not just luck, it’s what I’m doing, it’s about what I’m writing about.”

Sen. Sherrod Brown Reflects on Mike Honey's Work

In this photo, then-nominee Ketanji Brown Jackson (now U.S. Supreme Court Justice Jackson) is holding a copy of “All Labor Has Dignity,” a collection of Dr. Martin Luther King’s speeches on labor rights and economic justice, edited by Mike Honey.

U.S. Senator Sherrod Brown (D-OH) gave a copy of the book to Jackson when she visited his office as part of the nomination process. Both Sen. Brown and Justice Jackson have a long history of advocating for labor. “I’ve turned to Dr. Honey’s book over and over for guidance and inspiration from Dr. King’s powerful words and ideas about the dignity of work,” said Sen. Brown. “Not enough people understand Dr. King’s relationship with the labor movement, and the deep connection between workers’ rights and Civil Rights. It’s why I give the book to friends and colleagues and people I meet with — when more public servants learn this history, we get a more pro-worker government.”

Honey could have left UW Tacoma and taken any number of positions at larger, more prestigious universities. He didn’t. “There have been offers, and that’s partially where the Haley Professorship comes in,” said Honey.

He is referring to the Fred T. and Dorothy G. Haley Endowed Professorship in the Humanities, established in 2007. Honey was named the first recipient and has held the chair ever since.

“The mission of the professorship is to attract or retain someone who has a broad reach in humanities and cares about civil liberties civil rights and social issues. And so, when I got offered that, I thought, ‘Well, this is me, this is what I do.’”

By 2007, Honey had established himself as a leader in his field. By the end of the year he would be known as a public intellectual and one of the foremost MLK scholars in the world. This seismic shift is due to the publication of Honey’s book “Going Down Jericho Road: The Memphis Strike, King’s Last Campaign.” The book earned Honey the prestigious Robert F. Kennedy Book Award. “That book helped to change how people thought about King and got them to see him as a labor advocate as well as a civil rights advocate,” said Honey.

Honey started to get attention from national media outlets. He was interviewed by Terry Gross on NPR’s “Fresh Air.” Since then he’s been a regular in the press and has been quoted or published in outlets as various as the New York Times, Time, The Guardian and Smithsonian Magazine.

Despite all of his success, Honey doesn’t have his head in the clouds. He’s as dedicated as ever to researching and to passing that knowledge on to and through his students. “I feel kind of humble when it comes to teaching,” he said. “It’s a hard thing to do and it’s always different but it has a profound impact. Education can really change your life. If I hadn’t had higher education, I’m not sure how I would’ve turned out and I think that’s important to remember when you’re in the classroom.”

Keep Telling the Story

Mike Honey’s passion for knowledge and his dedication to the rights of all people won’t retire. How could they? These are part of him, as vital and important as blood and air. “All of my life, I have tried to be anti-racist, and not out of feeling guilty about the past or about my family. As King said, ‘Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.’ This is just what I believe in,” he said. “The freedom and labor movements are about the world I want to live in. It’s always been that way with me.”

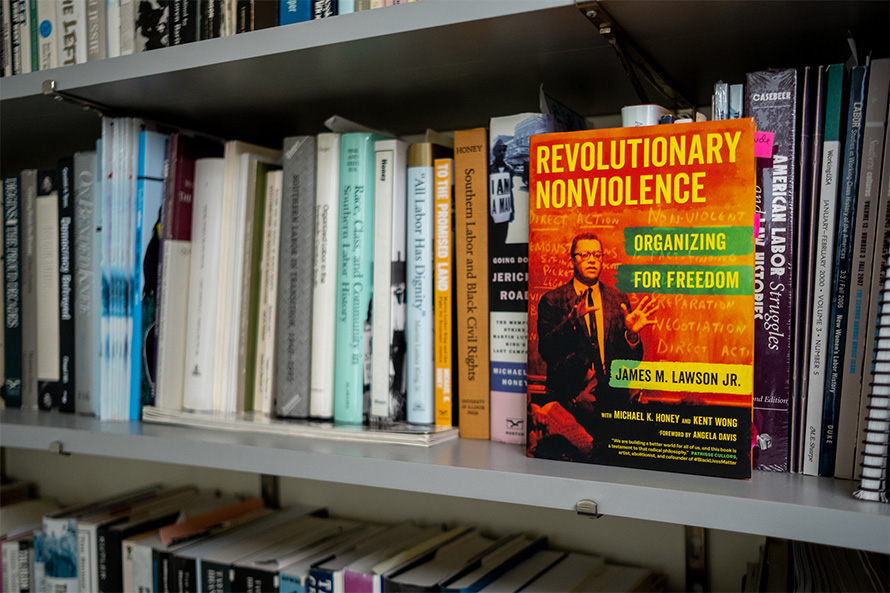

Honey isn’t retiring from life — he’s just co-authored a book called “Revolutionary Nonviolence: Organizing for Freedom” and is working on a memoir of sorts — but Honey is stepping down from his position at UW Tacoma. “It’s time to let a younger person have the job,” he said. “But I don’t expect to disappear.”

Honey has about ten chapters completed of his memoir/history of the 1970s. He is also doing a lot of work around non-violence with labor and civil rights activist James Lawson. This begs the question, why not slow down and enjoy the fruits of his past efforts? Well, a lot has changed since that smoke rolled into Honey’s jail cell, but he feels there is still work to do.

Certainly the last few years have shown that many of the problems Honey fought against in the 1960s and 1970s are still very much with us. Back then, Honey had a choice to make once he’d picked himself off the jail floor and was escorted outside. He could have decided he’d had enough. Facing the same choice now, Honey knows what he’ll do. “We have to keep telling the story, telling history, telling reality,” he said. “That’s education, and that’s what we’ve got to do.”