Multiple Versions of the Same Person

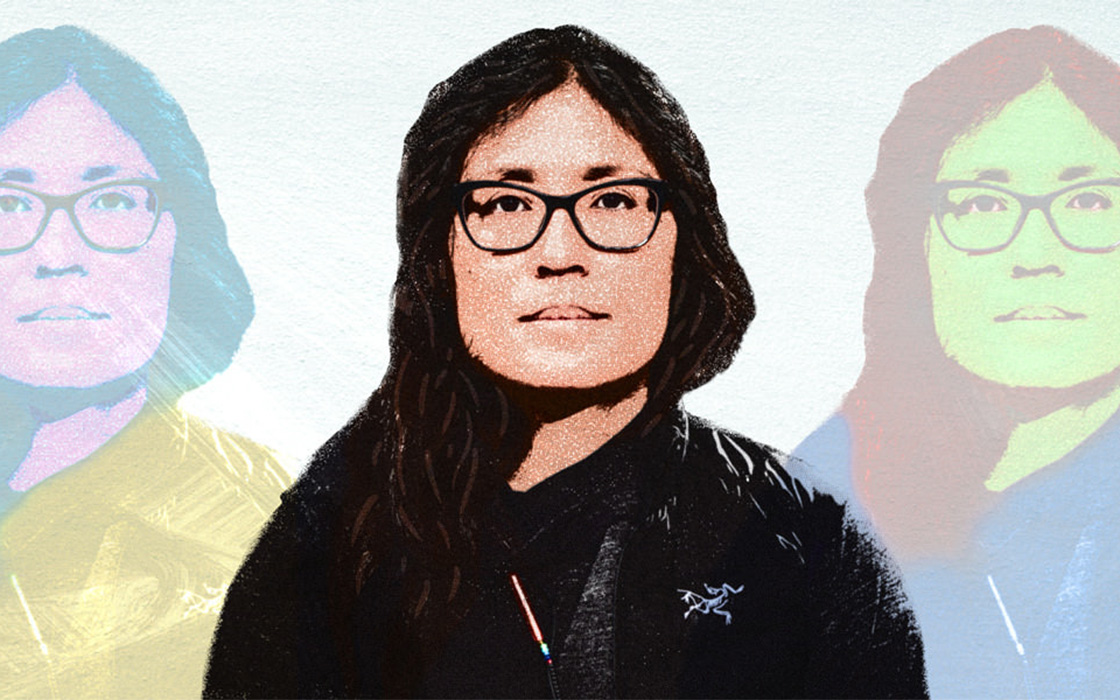

UW Tacoma faculty member Michelle Montgomery explores identity in her book about mixed-race American Indians.

Who are you?

Three little words, a question with many answers. “When people say ‘who are you?’ what they really mean is ‘what are you?’” said UW Tacoma Assistant Professor Michelle Montgomery. [Editor's note, Sept. 2020: Dr. Montgomery is now an Associate Professor.] Identity is a critical component of Montgomery’s work and the subject of her book Identity Politics of Difference: The Mixed-Race American Indian Experience.

Montgomery grew up in an American Indian community in Hollister, North Carolina. She’s an enrolled member of the state-recognized Haliwa-Saponi tribe and a descendant of the federally-recognized Eastern Band Cherokee. “I lived in a small community and never had to deal with the race politics of identifying myself as state or federally-recognized,” she said. “You didn’t need to walk around identifying yourself as Native, you were Native.”

Governments and tribes use blood quantum to determine who can be counted as an American Indian. So-called “Indian blood” is a complicated idea first enacted by the federal government as means of limiting tribal membership. The question of who is and isn’t an American Indian becomes more complex when a person is mixed-race. “You could be a descendant of multiple tribes, but if you don’t meet the blood quantum of one of those tribes then you’re just an American Indian without tribal enrollment,” said Montgomery. Montgomery is a mixed-race American Indian. “My dad is American Indian, African American and white,” she said. “My mother is Korean and Mongolian.”

“I’ve always embraced the sum of my parts, I’ve never been told not to.”

Montgomery earned a bachelor’s in biology at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University. A few years later she completed a master’s in plant pathology from North Carolina State University. After graduate school she got an internship at the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). “I wanted to work for the EPA,” she said. “They were doing all these great things in tribal communities, specifically around air quality.”

While at the EPA, Montgomery met a tribal elder from the Pueblo of Acoma tribe in New Mexico. “He said, ‘why don’t you come work for me?’” Montgomery packed her bags and moved to the Southwest to work as the manager of an air quality program for the Pueblo of Acoma. From there Montgomery took a position at the American Indian Science and Engineering Society (AISES).

The move from North Carolina to New Mexico provided Montgomery with a chance to pursue her interests which include education and the environment. The transition also exposed her to a type of identity politics that she hadn’t previously experienced. “I was being asked to prove I belonged, that I was ‘indigenous enough,’” she said.

In situations like this, “proof” can take multiple forms whether it’s genealogy, blood quantum or a tribal identification card. “Not only do I have a social security number, not only do I have a passport, not only do I have a driver’s license, now my government requires I identify myself as either state or federal,” said Montgomery. “What other race group is required to show proof?”

Montgomery’s tribe doesn’t consider blood quantum when deciding who is and isn’t a member of their community. The practice has both defenders and detractors. Montgomery says conversations about blood quantum need to be viewed within the proper context. “These decisions are based on historical trauma. You could say that this system creates outliers, that it marginalizes a generation of people who may not fit the criteria, but, at the same time, you could say it’s empowering, a tribe’s inherent right is to decide its enrollment criteria.”

The effect of blood quantum is a reverse of racist one-drop rules that were used to disenfranchise African Americans. “If you had one drop of African American blood, or African blood, you were deemed African American,” said Montgomery. “It’s the opposite for indigenous people whereby less “native” blood limits how you’re viewed and what you can be become with certain communities.”

“I am constantly gifted the word, the phrase, ‘I’m impressed.’ ”

Montgomery takes multiple buses to get from her home in Redmond to campus. “I dress very casually and I’m a dark skinned person,” she said. “People see me and they think I’m displaced so they don’t want to sit beside me.” Montgomery doesn’t do it all the time, but on occasion she reaches out to those around her on the bus and strikes up a conversation. “We get to chatting and it comes up that I’m an American Indian and work at the University of Washington Tacoma,” said Montgomery. “Often, the response I get is ‘I’m impressed.’”

There’s a lot to unpack from Montgomery’s experience but a key takeaway is how she and other mixed-race American Indians are viewed by others. She says identity politics play out differently in different settings. Montgomery taught math and science at a high school in Grants, New Mexico after leaving AISES. Grants is a small reservation border city in Northwestern New Mexico. “There are a lot of negative stereotypes about indigenous communities in border towns,” says Montgomery.

Montgomery decided to address these issues head on, often in the classroom. She engaged her students in conversations about race. “Not only did I have a lot of American Indian students gravitate toward me but I changed a lot of stereotypes of reservation border towns by non-indigenous people,” said Montgomery.

Physical appearance for mixed-raced American Indians can be empowering and limiting. Montgomery describes herself as the “phenotypic stereotype of what a Native person should look like.” This “look” can be a benefit in certain communities and a perceived liability in others. “Someone who is Native but looks more phenotypically European will face a different reality than someone who is Native but looks more phenotypically African American,” said Montgomery. “One group may have power and privilege that the other doesn’t.”

The identity politics for mixed-race American Indians also swings the other way. In her book, Montgomery tells the story of mixed-raced students at a tribal school in New Mexico. “Those who are mixed-race, who phenotypically look like the dominant culture, often felt that when they went into an American Indian community they weren’t accepted,” she said.

“I want to call people into a conversation versus call them out on it.”

Montgomery’s book is part scholarship, part therapeutic exercise. “This book was a healing process for me,” she said. “As a mixed-raced person you’re constantly wondering if you’re owning too much of one part of your skin over the other.”

Montgomery is currently working on another book: Resilience and Sustainability: Traditional Ecological Roots of Indigenous Studies. She hopes her work is informative, that it gets people to consider hard questions about what it means to be American Indian. “I think we can have critical, reflective conversations, and we can debate,” she said.

Which brings us back to the question posed at the beginning of this article. Who are you? More specifically, who is Michelle Montgomery? Through our conversation, here is what I gleaned. Montgomery is a: scholar, mixed-race American Indian, woman, member of the Haliwa-Saponi, descendant of the Eastern Band Cherokee, author, scientist, educator, environmentalist, outdoor enthusiast, commuter, activist, climber, North Carolinian, self-described “tomboy,” novice sailor, assistant professor.

One question with many answers.