Rolling Up His Sleeves

Charles Emlet's experience as a social worker lead him to UW Tacoma and a career that changed our understanding of aging in vulnerable communities.

Charles “Charley” Emlet isn’t afraid to roll up his sleeves and get to work. Emlet spent most of his formative years on a small family farm about twenty miles south of Fresno, California. “We grew grapes, peaches, and walnuts,” he said. “My grandmother owned it, my father farmed it.”

Farming isn’t so much a job as it is a lifestyle. “My father only took a couple of vacations and none of them lasted more than two or three days,” said Emlet. With farming there are always seeds to plant or crops to harvest, fields to till or equipment to fix.

As the oldest of two siblings, Emlet’s future looked all but certain. “My first car was a Ford tractor – and I was 12 years old,” he said. “By that age I was ploughing fields and setting irrigation pipes in cotton fields.”

The year is 1968. Emlet is 15. His life consists of school, hanging out with friends and helping around the farm. The 1960s is an era defined by change and social unrest. Historically, 1968 ranks as one of the more tumultuous in modern American history. Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy are both assassinated in 1968. In January of that year, North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces launched the Tet Offensive against more than 100 South Vietnamese cities and outposts. 1968 is also defined by protests across the United States, most notably at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

For the Emlet family, 1968 is a time of sorrow and profound loss. “My grandmother died and I lost my father forty days later,” said Charley Emlet. Until that point the farm had been in the Emlet family for more than 50 years. “We, my mom, sister and I, stayed on the farm for a little while but ended up having to sell it,” he said.

The trio moved to purchase a home in the small town of Kingsburg, California. “My mom did seasonal work,” said Emlet. “We lived off that and Social Security survivor benefits. I worked two jobs after school to help out financially. It was tough but we supported each other and got through it.”

Another way to be a man

Emlet graduated from high school a few years later and enrolled at California State University, Fresno (CSUF) where he planned to pursue a degree in agriculture. It’s during Emlet’s sophomore year at CSUF that the life he could have led and the life he ended up leading once again diverged. “I took this class and, to this day, I don’t know why I took it,” he said. “It was called something like ‘Introduction to Social Work.’”

Emlet spent most of his young life surrounded by a particular kind of man. “They were farmers,” he said. “Most of them were World War II vets and they were hard men.” By contrast, the professor who taught that intro to social work course, “was a licensed clinical social worker who worked with people who had severe mental illness. He was kind and he listened. He was just so starkly different from all the other men in my life and I went, ‘Wow, this is something else,’” said Emlet.

Origin stories are big on finding connections between who a person is and who they were. This is easy to do with a team of script writers and a story that has to go a certain way. Real life isn’t as clear cut or pre-determined. For whatever reason, maybe it was the trauma that Emlet experienced combined with finding someone whose job it is to care for others -- or perhaps seeing another way to be a man in the world – that sparked something inside Emlet. Maybe none of these scenarios inspired what happened next. “I took another class from that professor,” said Emlet. “I also did some volunteer work with him that involved meeting with people in the community that had serious mental health issues.”

By the beginning of Emlet’s junior year he’d changed his major from agriculture to social welfare. “I never looked back,” he said.

An earlier pandemic

Emlet completed both a bachelor’s and master’s degree in social welfare and social work at CSUF. Afterwards he took a position as a social worker with Sierra County Mental Health Services. Emlet then worked as a medical social worker with the Solano County Department of Public Health before being named the program director/senior medical social worker at the Solano County Health & Social Services Department.

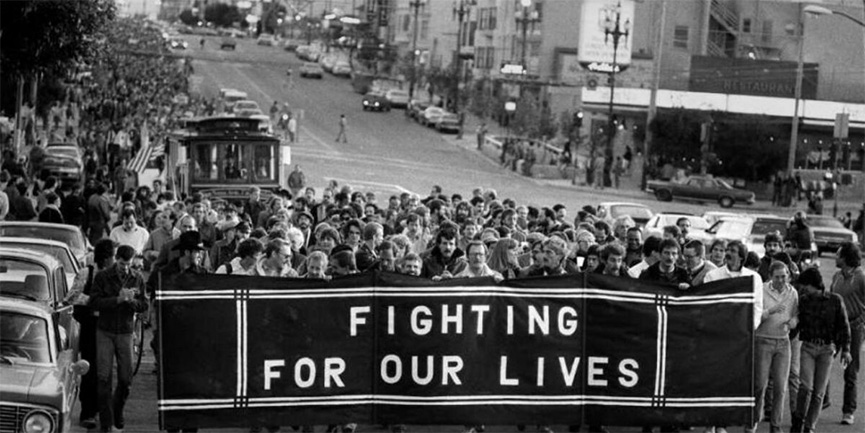

Emlet’s work in Solano County focused on older adults and people living with end-stage HIV disease. It’s important to remember that the world looked very different for those living with HIV/AIDS in the 1980s and early 1990s. There were few treatment options and those that were available came with side effects. “Some people would say to me, ‘The meds are worse than the disease’,” said Emlet.

The early years of the HIV/AIDS crisis were rife with misinformation about how the disease spread. Those who became infected were ostracized while entire groups, most notably the LGTBQ+ community, became targets of ridicule and blame. “I saw people that were just invisible,” said Emlet. “Nobody was seeing them.”

Among the invisible were older men and women living with HIV. “After a while I started to notice that there were older people on our caseload who wouldn’t accept the same kinds of services that we normally referred young people to,” said Emlet. “The gerontologist in me wondered what was going on. There was this intersection between HIV and aging that I didn’t understand.”

Emlet decided to dig into the issue. “I did some unofficial research and chart reviews,” he said. “From that I decided I wanted a second career in academia.” Emlet received admission to Case Western Reserve University to pursue a Ph.D. in social work. Emlet knew he wanted to understand the experience of older adults living with HIV. “As a doctoral student I was told this wasn’t an issue,” he said. “Well, I think there’s a part of me that’s something of a maverick. If you tell me I can’t do something there’s a decent chance I’m going to try anyway.”

Insights into aging

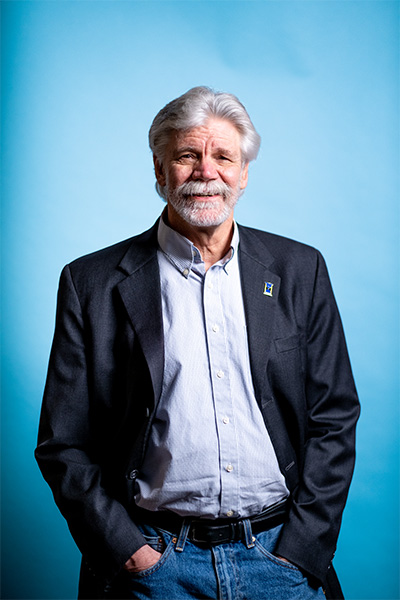

Emlet completed his Ph.D. in 1998 and came to UW Tacoma a year later. “I had a colleague of mine that was a couple of cohorts ahead of me at Case Western and he said, ‘You should really look at UW Tacoma and Marcie Lazzari as a place to go’,” said Emlet. “So, I called her [Lazarri] up and she encouraged me to apply and I was fortunate enough to land a job here.”

Emlet arrived at UW Tacoma when the campus consisted of only a few buildings. “During my interview I remember saying, ‘Where’s the campus?’ And the person I was meeting with said, ‘This is the campus.’” The institution, along with Emlet’s reputation, grew over the next 23 years. Emlet is a renowned and respected scholar. His work focuses on aging, specifically among older adults living with HIV as well older members of the LGTBQ+ community.

Once derided as “not an issue,” Emlet’s research interests have garnered him both praise and support. In 2001 the John A. Hartford Foundation named him a Hartford Geriatric Social Work Faculty Scholar. A few years later, in 2006, Emlet was named the inaugural recipient of UW Tacoma’s Distinguished Research Award.

Emlet and University of Washington Professor Karen Fredriksen Goldsen received funding from the National Institute on Aging. “We created something called the National Health, Aging, Sexuality, and Gender Study,” said Emlet. “It’s a longitudinal study that looks at aging in vulnerable communities.” In 2012 Emlet received a Fulbright Scholars award to study successful aging in long-term HIV survivors living in Ontario, Canada.

Locally, Emlet’s interest in issues affecting older populations lead him to get involved with The Puyallup Area Aging in Community Committee. The group worked with city leaders to get Puyallup designated an American Association of Retired Persons/World Health Organization age-friendly city. “An age-friendly community is a good place to grow old,” said Emlet. “They’re age-friendly attitudinally as well as structurally.”

In terms of how cities are designed, Emlet gives the example of a crosswalk signal that is too quick and changes while an 80-year-old is crossing the street. “In this case, its [the signal] probably also going to catch a 28-year-old mom with three kids in tow,” he said.

It’s important to remember that Emlet grew up in a multi-generational household. “The grandmother who owned the farm was an immigrant and classically Swedish,” he said. Emlet’s other grandmother lived nearby. “She was a devout Roman Catholic and very much believed in helping others,” he said. “She was the one who taught me how to be quiet inside.”

Mainstream representations of aging and the elderly use the same brush to produce the same painting. Those past retirement age are often shown to be weak, needy, lonely, sad, angry or some combination of these traits. “There’s this idea that older people are the takers, they’re consuming, they’re needing the support and that creates a sort of view of frailty and inadequacy,” said Emlet. It’s easy to see older people this way if they’re kept at a distance and preserved in stereotype. “The research tells us that the more you’re around older people, the higher you value them and the more you see them as contributing and lively,” said Emlet.

Being mindful

Charley Emlet rolled up his sleeves more than sixty years ago. He’s kept them that way ever since whether he was toiling away in a field or toiling over a research paper in the wee hours of the night. Emlet plans to retire at the end of the school year. Academia is his second career. “I don’t plan on starting a third,” he said.

Some retirees spend their post-work life keeping busy. “So many people are uncomfortable being still and they retire and immediately full up their calendar,” said Emlet. “That’s not my M.O..” An avid outdoorsman, Emlet is committed to spending his time kayaking or hiking. He’s also hoping to spend more time with his grandchildren.

Emlet has a lifelong interest in spirituality and meditation. He developed those interests into a course he created at UW Tacoma called “Spirituality and Social Work Practice.” The course looks at spirituality from different perspectives including how practices like mindfulness can impact how social workers do their jobs. “Mindfulness can make you a better clinician, as you are more present with people and less likely to be thrown emotionally,” said Emlet.

In many ways, Emlet’s life has been in service to others. It’s literally been his job. Emlet will always care — it’s in his nature. “A lot of times when people retire they talk admirably about finally having time to give back to the community,” he said. “I spent my career both academically and as a social worker trying to help marginalized communities and, so, I feel like here’s the opposite. Here’s an opportunity for me to spend more time on the Aikido mat, to spend more time being quiet in the mountains and seeing what the next whatever few years, many years — I don’t know — have to offer.”