Never Stop Walking

At 13, Elavie Ndura had a goal to become a university professor and walked for three days to go to school. Today, she lights the way to education for countless others.

It’s a little after three in the morning but 11-year-old Elavie Ndura is already awake. She’s excited — and a little nervous. The energetic Ndura is a font of curiosity that is rivaled only by a fierce determination to succeed.

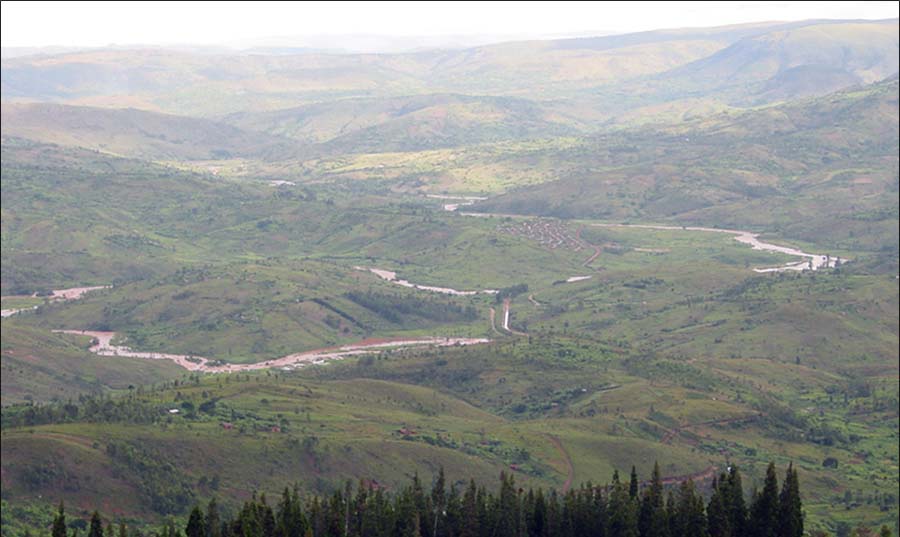

Ndura is the oldest of six siblings, all of whom are awake, if not quite alert at this hour. The family stands outside their small hut. It’s dark and cool at this hour. The rolling hills of this part of Burundi are flattened by the shapeless early morning.

Ndura’s mother brings her daughter in for a warm embrace. The moment is long by hug standards but also painfully short. The adolescent wipes away the tears crowding the corners of her eyes. She hastily hugs her brothers and sisters in turn and promises to see them soon. Ndura needs to get moving, to start walking, lest her courage fade.

Ndura, along with her father and a guide, set off into the cold, ink-stained unknown. Ndura’s father is paralyzed on one side of his body. The guide carries a wooden case that contains items Elavie will need. “My family did not have money for a suitcase, so my father asked a local carpenter to make a case out of wood,” she said.

Inside the case are a pair of flip-flops. Shoes are required at the boarding school. “The flip-flops were the only thing my family could afford,” she said. “I didn’t want to ruin them so I put them in my suitcase and walked barefoot.”

The eighty-mile journey to the boarding school takes several days. The trio walks from roughly three in the morning to seven at night. They veer away from the main roads, choosing instead to take short cuts through villages and across fields of cassava, bananas and beans. “This was before the war so Burundi was very safe,” said Ndura. “At the end of each night we would walk up to a residence and ask if they would allow us to spend the night. They [the residents] would spread out a grass mat in the entrance and that’s where we’d rest.”

The multi-day trip is long and difficult. Muscles ache and stomachs groan. The early morning sun brings warmth that turns to blistering heat only a few hours later. Ndura keeps going, keeps striving because she knows something, a truth that someone so young shouldn’t need to understand. “We were poor,” she said. “We had food because we had a farm but that could change with the season.”

Ndura’s father had a fifth-grade education. Her mother never went to school. “Education is not a right in Burundi,” said Elavie Ndura. “You had to fight for it.” Ndura’s parents instilled a love of education in their children and charged their oldest, Elavie, with setting the example for others to follow. “I had a responsibility to be the light for my siblings,” she said.

Ndura excelled in primary school. “I was one of the rare sixth graders who passed the national exam on my first attempt,” she said. This success opened the door for Ndura to continue with her education, but this meant leaving home to attend a boarding school eighty miles away. “It was hard but I knew the only way to get my family out of that hut, out of that poverty, was through education,” she said.

Legacy of Colonialism

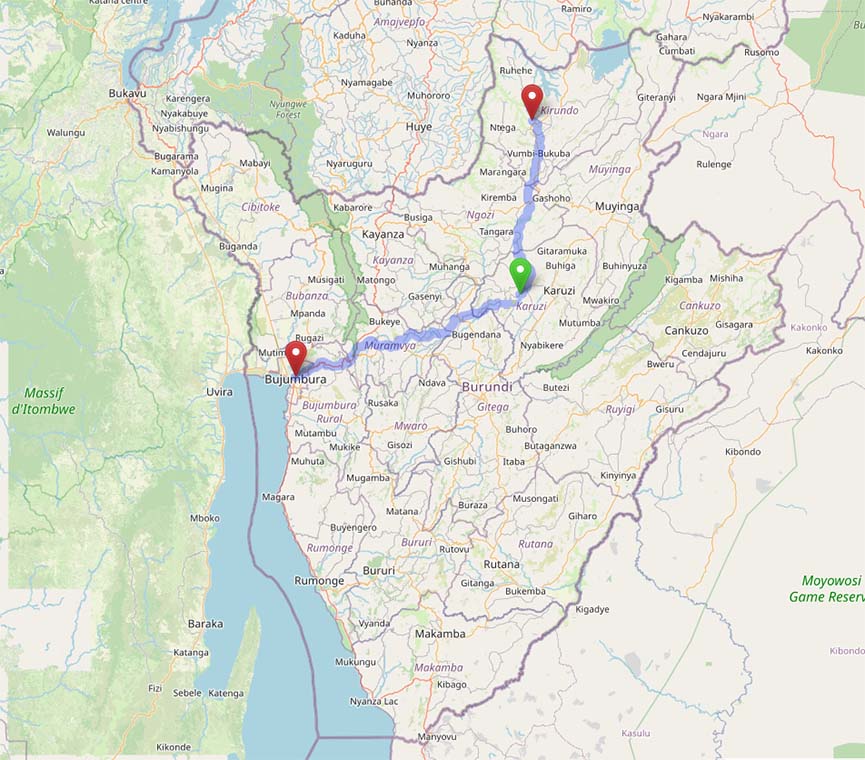

Distance wasn’t the only thing standing between Ndura and her education. There was also poverty and conflict. All of these obstacles can be understood by looking through the lens of history. Europeans arrived in the Kingdom of Burundi (now Republic of Burundi) during the mid-1850s. Germany ultimately invaded and took over the country, which is about the size of Maryland, by military force in 1899 and retained control until 1916 when Belgian troops captured the area during World War I. Belgium used a system known as indirect rule that allowed local leaders to assume day-to-day control while the Belgian government assumed control over things like taxation and foreign policy.

Indirect rule lasted until 1962 when Burundi achieved full independence. It’s important to understand the impact of colonialism. In 1923, the League of Nations combined the separate nations of Burundi and Rwanda into one. These countries were, and still are, populated by three distinct peoples, the Hutu, Tutsi and Twa. The Belgian government threw their support behind the Tutsi and allowed them to rule over the Hutu and Twa. At the time the Hutu were a clear majority of the population.

Rwanda and Burundi separated in 1962. What followed was decades of ethnic violence between the Hutu and Tusti. The period was marked by war and genocide in both countries. “I had to fight harder because I was a Hutu in a country that privileged the ethnic minority, the Tutsi,” said Ndura. “Everything was against me.”

“I’m a social justice practice leader by birth.”

There were obstacles in Ndura’s path, but she never stopped moving. Ndura thrived in boarding school. After graduation from high school she was accepted into the University of Burundi where she earned a Bachelor of Humanities and Social Sciences in English Language and Literature.

Ndura took a break from higher education to start a family. She married and the couple had two children together. Ndura returned to school in England to obtain a master’s degree in education from the University of Exeter. Ndura’s husband and children stayed in Burundi.

A tenuous peace in Burundi helped make it possible for Ndura to continue with her education. That peace ended in 1988 when another round of violence targeted at Hutus erupted in the country. “I lost a sister during the violence as well as my husband,” said Ndura.

The loss of her sister and husband were devastating for Ndura. The then-29-year-old widow had two small children to support. “I didn’t think I could get back up and continue walking,” she said. Amid the tears and anguish, Ndura remembered a list she once made. “When I was 13 years old, I wrote down ten life goals that I wanted to achieve and one of those goals was to become a university professor,” she said. “I had dreams,” she said. “My goals became more urgent then, I didn’t know how I was going to reach them, but I would reach them.”

Professor of Education

Ndura moved to the United States to pursue a doctoral degree in education from Northern Arizona University. Going to classes sometimes meant bringing her children along. Studying happened in the evening after the children went to bed and continued until long past midnight.

In 1990, Ndura took a big step toward achieving her goal of becoming a university professor when she accepted a position as adjunct instructor with NAU. Ndura stayed in that role for 11 years before serving as assistant professor of multicultural education at the University of Nevada, Reno. Ndura remained in that position until she moved to George Mason University (GMU) at the start of the 2005 school year.

It was at GMU that Ndura achieved the rank of full professor. During her 12 years at George Mason, Ndura also established herself as a powerful voice for diversity, equity and inclusion. From August 2015 to August 2016 she served as GMU’s presidential fellow for diversity and inclusion.

Ndura left George Mason to assume the role of vice president for equity, diversity and inclusion at Gallaudet University, the nation’s leading educational institution serving the Deaf community. Before coming to UW Tacoma, Ndura also worked as the associate vice president for diversity, equity and inclusion and campus diversity officer at California State Polytechnic University, Humboldt (Cal Poly Humboldt).

Careers in academia often run along more than one track. University faculty teach, volunteer to serve on committees and conduct research. The same is true of Ndura. On top of her three degrees, Ndura also earned a graduate certificate in conflict resolution from George Mason. Among her many accomplishments, Ndura has been honored with multiple Fulbright fellowships, a Woodrow Wilson Center fellowship, and a peace educator of the year award from the Peace & Justice Studies Association.

Building Relationships

Ndura keeps a pair of walking shoes on the bottom shelf of a bookcase inside the Office of Equity & Inclusion. Ndura officially started as UW Tacoma’s new vice chancellor in that office on August 1.

Ndura plans to do a lot of walking around campus, both to get acquainted with her new home, and to meet with people. When Ndura first started at Cal Poly Humboldt she embarked on a 120-hour listening tour. “I listen a lot because I need to understand the people and the place in order to develop relationships,” she said. “The work of diversity, equity and inclusion is not the work of one person, it’s a community undertaking and you cannot work with people you don’t understand.”

Building relationships is part of a larger goal established by UW Tacoma Chancellor Sheila Edwards Lange. “During my interview I asked Chancellor Lange what are the three things that she would like me to start working toward on day one,” Ndura. “The Chancellor responded very fast. She said, ‘Community building, community building and community building.’ She clarified and said, “When we have a healthy community, everything becomes possible.’”

In some respects, Ndura has a blueprint to work with. “We have data from the campus climate survey and the UW Diversity Blueprint, so we know the direction of the work that we need to do,” she said. “We cannot address all the issues raised in the climate survey at the same time, so we will need to prioritize.”

Ndura hopes to get help prioritizing by creating an Equity & Inclusion Council made up students, faculty, staff and community partners. “This council will help inform how we proceed but it’s also a communications strategy,” she said. “Messages from the Office of Equity & Inclusion will have a conduit and will go straight to different units and then issues and voices from each unit can came straight to my office.”

Being the Light

Elavie Ndura has never stopped walking, not really. Nowadays, the journey isn’t so much about herself. One of the goals the 13-year-old Ndura set for herself was to pay for her siblings to go to college. She did that. All of her surviving brothers and sisters received a college degree, thanks in part to Ndura and the education she received which helped make her family’s success possible.

Ndura has always been bullish about education and has little patience for obstacles. “Anything, anyone, who attempts to do something that blocks educational access -- my voice comes out, peacefully, but strong,” she said.

Several years ago, Ndura’s parents charged their oldest child with a responsibility. She needed to be the light that others could follow. Ndura did that for her siblings and now she does this for students at UW Tacoma. “We are here to be the champions, to be the guide to our students,” she said. “We need to support them, open the doors and keep them open. It’s our duty to put in place the policies, the processes and the pedagogies that will create an environment where our students can achieve their dreams.”

In 2014, Elavie Ndura delivered a lecture on social justice and peace while serving as a professor of education at George Mason University.