Geographers seek stories of Seattle's pre-AIDS gay communities

Larry Knopp, professor and director of interdisciplinary arts and sciences, and Michael Brown, a geography professor at UW in Seattle, are piecing together how policies related to alcohol and public health shaped gay and lesbian life in Seattle pre-AIDS.

(This story was originally published on June 14, 2012 by the UW News & Information office. Read the story on the UW News site.)

With gay communities thriving in Seattle today and as many as 350,000 expected to attend the Seattle Pride Parade June 24, some might not realize how deeply homophobia and heterosexism reached into people’s daily lives in the city not that long ago.

They may be surprised to hear that as recently as the 1950s and ’60s lesbians were required to wear feminine clothing, gay couples curtailed their affectionate behaviors in bars and restaurants, and sodomy — until 1976 — was a crime.

But for others, especially those who were part of the Seattle gay community in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, these stories come as no surprise. And it’s the memories of those folks that two University of Washington geographers hope to tap as part of a new study, “Biopolitical Geographies.”

Michael Brown, a UW geography professor, and Larry Knopp, professor and director of interdisciplinary arts and sciences at UW Tacoma, are piecing together how policies relating to alcohol and public health shaped how gays and lesbians in Seattle carried out their lives during the pre-AIDS era, before 1983.

Gay people stayed under the radar back then, and much remains to be learned about gay life at the time.

“AIDS changed a lot of things; it made the gay community become more empowered,” Brown said. “People were more comfortable talking about sexually transmitted diseases and there was more awareness that people live sexual lives.”

He and Knopp are studying how two government agencies — Public Health Seattle & King County and the Washington State Liquor Control Board — interacted with gay people and the spaces they inhabited during a time when gay life was often carried out in secrecy.

“I hope that the project will help us better understand the subtle ways that our consciousness and behaviors are shaped and normed by bureaucratic practices,” Knopp said.

The geographers want to know how these government agencies charged with seemingly non-political, humdrum tasks pertaining to daily life actually reflected and shaped social, cultural and political attitudes relating to marginalized populations, and how members of those populations often internalized such attitudes.

Knopp, recalling a study he and Brown published in 2010, said that similar historical evidence has been found before. The geographers examined the Seattle public health department’s efforts to control sexually transmitted diseases during World War II. Their findings show how women were stigmatized: the department’s monthly health reports, aiming to make sense of how disease was spread, generally labeled men as civilians or soldiers and women as prostitutes, waitresses or wives.

“Through these categories, there’s the notion that men are the victims of venereal disease and women are the carriers,” Knopp said. The categories implied that public health officials couldn’t imagine women as recipients. Rather, “women are the problem that needs to be controlled,” he said.

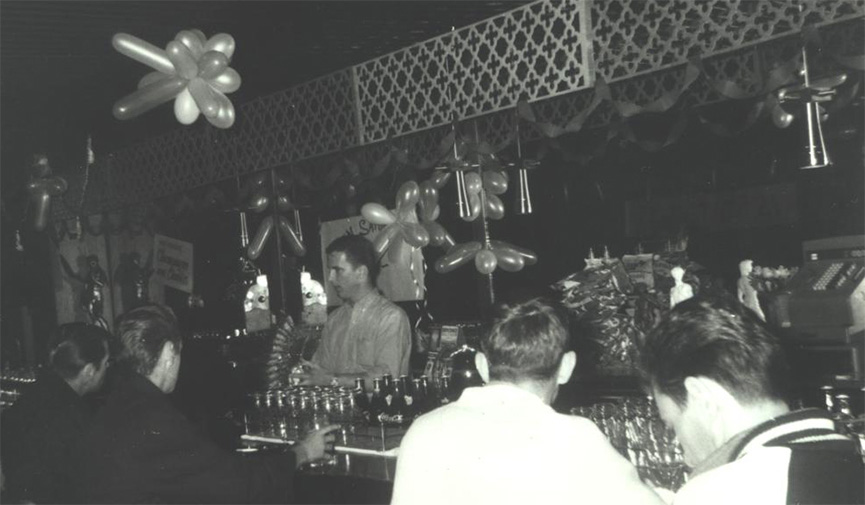

For their new study, which is funded by the National Science Foundation, Brown and Knopp are collecting stories from people who went to, owned or were otherwise familiar with the city’s gay bars and restaurants and sought out gay-friendly medical treatment from after World War II until about 1983.

They also want to interview past and present public health officials, people involved in disease prevention before AIDS emerged, and others who experienced how the public health department and liquor board exercised their authority in the mid-20th century.

In confidential interviews lasting about an hour, the researchers ask about what people saw at gay bars, what patrons could and could not do while there, and who enforced any behavior restrictions gay bars had in place.

For sex-related health problems, including STDs, did married gay men skip their family doctor and instead go to a gay-friendly health clinic, such as Capitol Hill’s Country Doctor Community Clinic?

The 50 people interviewed so far have offered insights that include:

- “Blue laws” that regulated liquor sales could have quite an effect on gay and lesbian spaces: they dictated the floor plans of taverns, their visibility to the street (important if people were “in the closet”), and even the conduct of patrons.

- Lesbians were required to wear at least three articles of feminine clothing, or else they risked being kicked out of a bar for appearing too “butch.”

- Health department investigators could be discreet, but were sometimes known to call the homes of closeted gay men who sought treatment for STDs — perhaps leaving a phone message with unassuming wives — to inquire about other sex partners.

“What’s emerging from our research is an understanding by bar owners and patrons of standards of behavior that had to be adhered to,” Knopp said. The liquor board had broad authority to control the conduct of patrons and even declare decorations in bars or restaurants to be too sexually suggestive, he added.

The board was allowed to enforce “the spirit of the law as well as the letter of the law,” Knopp said, giving plenty of wiggle room to reflect the pervasive homophobic attitudes at the time.

Like the TV character Sal Romano in “Mad Men,” many gay Seattleites in the pre-AIDS era were in the closet, married and outwardly living as straight people. They feared losing their jobs or housing, being physically assaulted, being subjected to derision from family and friends, and other consequences of living an openly gay life.

Even in liberal Seattle, many people at the time considered homosexuality a moral failure or mental illness.

“Just because it’s a liberal city doesn’t mean that there wasn’t moral regulation,” Brown said. “We want to know how gay men and lesbians interacted with local policies related to day-to-day life.”

The researchers hope to finish interviewing people by spring 2013 and plan to write a book on their findings.