DeAnn Dillon: The Undiminished Spirit of Sharing

DeAnn Dillon is a mom, a teacher, an auntie, a Native American, a legislative aide, and a doctoral student. She is also a giver of energy.

June 2023 update since this story was originally published:

DeAnn Dillon has now completed her doctoral degree in educational leadership.

The state capitol campus in Olympia is a sprawling maze of buildings. These behemoths impress and intimidate visitors with their names — “Temple of Justice” — and their appearance. The most well-known of these structures is the Legislative Building and its 287-foot-tall dome. The building is a mass of concrete, brick, steel, sandstone and marble. It’s both elegant and serious, grandiose and practical.

The dome dominates the city skyline. The artificial 1.9-mile-long Capitol Lake sits just down the hill from the capitol campus. Viewed from the lake’s promenade, the towering dome looks more like a medieval castle then a home for representative democracy at the state level. The inside can be just as imposing. Architecture aside, the place is busy with professionals dressed in ties, button up shirts and tapered slacks.

Into this world came DeAnn Dillon. “I still had the same color hair (red), I’m full of tattoos, I’m loud, and in your face,” she said. “Here I come walking into a building that was made to erase part of who I am and who my people are.”

The year is 2017 and Dillon has recently graduated from UW Tacoma with a degree in ethnic, gender and labor studies. This is her first day as intern for State Senator John McCoy. McCoy retired from office in 2020. A member of the Tulalip Tribes of Washington, McCoy served in the Washington State Legislature for 17 years, 10 in the House of Representatives and seven in the Senate.

Besides being a state senator, McCoy also taught classes at The Evergreen State College in the Master of Public Administration (MPA) in Tribal Governance program. “Every Indigenous person that I knew in higher education or in the state legislature went to this program,” said Dillon. “I decided I needed to know what this program was about.”

Dillon earned her MPA in tribal governance from Evergreen. She started working at the legislature while she worked on her master”s degree, first as a legislative intern then as a legislative assistant. McCoy”s decision to retire left Dillon facing an uncertain future. “I was going to lose my job,” she said. “That’s when Danica [Miller] reached out and introduced me to the educational leadership doctoral program.”

Defacto Parent

Dillon is a citizen of the White Earth Nation (also known as the White Earth Band of Ojibwe). The tribe is located in North Central Minnesota. Dillon’s great grandparents belonged to the White Earth Nation but moved from the area to the Pacific Northwest in part because of the Indian Relocation Act of 1956. The federal policy eliminated government support for tribes. It also ended the protected trust status of all Native-owned land. The policy was designed to break up Indigenous communities by ending government assistance and offering incentives to individuals and families to move to larger, more urban areas.

Dillon was born in Washington but grew up in the San Francisco Bay area. She is the oldest of four kids. “I came from teenage parents,” she said. “They were 15 when they had me and were dealing with their own mental health issues and then to add a screaming baby on top of that — it was hard.”

Dillon became a de facto parent to her younger brothers and sisters. She looked after them, made sure they were fed and did their homework. “I’m a mother at heart,” she said. In high school Dillon met the man who would become her husband. They’ve been together for more than 20 years and have 10 children, six of whom are adopted. Dillon and her husband are tribal foster parents. Among their six adopted kids are two sets of siblings. “We didn’t want to break up the family,” she said.

Non-linear Path

Success isn’t guaranteed. Achievement operates on its own timetable and every individual’s clock is set to a different time. Dillon graduated high school and enrolled at St. Martin’s University. She planned on studying history. “A lot of history degrees don’t include Indigenous studies,” she said. “I didn’t want to learn anyone else’s culture. I wanted to be a historian for Indigenous people.”

Dillon eventually left St. Martin’s. She had a young family to take care of and needed to take a step back from higher education. Dillon later returned to school, this time completing her associate’s degree at Tacoma Community College before transferring to UW Tacoma. She came to campus in 2015 to continue her degree in history. “Then I had a set of twins and they were born bilaterally deaf,” said Dillion. “So that kind of put a halt on everything.”

The non-linear path is neither right or wrong. After all, this path is a person’s life and discounting its circuitousness minimizes the experience. Dillon did graduate, but not with a history degree and not in four years. “It took me 10 years to get my undergrad,” she said. “I like to tell others to ’Just keep pushing and get it done.’ ”

It’s hard to know what changed for Dillon, but she got into a groove and hasn’t left. One reason could be the influence of UW Tacoma Associate Professor Danica Miller. “She was my very first Indigenous professor,” said Dillon. “Seeing someone that represents who you are and what you came from in that position was mind-blowing.”

Dillon and Miller developed a relationship that later expanded to include Associate Professor Michelle Montgomery. “They both advocated for me and became part of my community.” Jump ahead a few years and the call from Miller was at once a casual check-in as well as conversation between mentor and mentee.

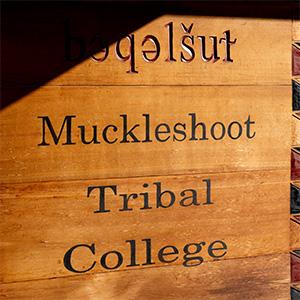

Dillon returned to UW Tacoma in the fall of 2020 to pursue an educational doctoral degree (Ed.D.). Dillon is one of 13 students in the inaugural Muckleshoot cohort. The cohort is a collaboration between the Muckleshoot Tribal College and UW Tacoma’s School of Education. Courses are built around Indigenous-centered curriculum as well as Indigenous approaches to teaching and learning. “The professors are all Native American as are other members of the cohort,” said Dillon. “I’m finally part of a classroom where I’m not the token Native, the one who everyone looks at as the voice of all Native people.”

About that groove Dillon is in. Well, it just got a little deeper. This past summer Dillon received an Indigenous Teaching Fellowship, supported by the School of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences and the UW Center for American Indian and Indigenous Studies (CAIIS). As part of the fellowship, Dillon will spend this academic year teaching introductory courses in Indigenous Studies at UW Tacoma. The opportunity gave Miller and Dillon a chance to work with each other: “As an educator, my goal is to give everybody a door to open,” said Dillon. “However, you have to open those doors. I will show you how and where but you need to follow the steps to further educate yourself.”

Getting a doctoral degree is difficult. Students can expect to spend long hours reading, researching, studying and, in Dillon’s case, teaching as well as grading. Dillon’s task seems even more challenging considering she is helping raise 10 children while going to school and working full-time as casework coordinator for the Senate Democratic Caucus. “I’m the first person in my family to graduate high school, so graduating high school and getting as far as I am now is very unreal for my family,” she said. “It’s important that my kids see me go through this. They see me struggle, but if I can do it with 10 children, then hopefully they see they can do it as well.”

It seems fitting that Dillon wants to be a professor. Her reservoir of caring is full to the point of overflowing. She’s a mother, but she’s also something else. Dillon’s husband and their children are citizens of the Puyallup Tribe of Indians. DeAnn Dillon is active within the Tribe and is always looking to lend a hand. “I consider myself a community teacher, an auntie to many,” she said. “That’s the energy that I like to give to my community. I may not be your mom, but I will scold you like an auntie and then give you candy afterwards.”

Jump back to the beginning and the first time Dillon walked into the Legislative Building as an intern. She mentioned the echo inside the chamber, the echo of footfalls, muttered conversation and the persistent low-level din of the legislative process in action. Dillon is loud and in a place of echoes a person with such vibrance is amplified, their voice, indeed their entire persona, fills the space until it cannot be contained by a physical structure. Such personalities break free; indeed, they have a spirit that can be shared without being diminished, one that lifts those who climb and those who want to but don’t know how to get started. Combined with others, that individual echo becomes a chorus.

Main Content

Indigenizing Higher Education

UW Tacoma's School of Education and the Muckleshoot Indian Tribe have signed a memorandum of agreement that will bring a doctoral program to the tribal college.

Main Content

Reclaiming Higher Education

The Indigenizing Pedagogy Institute is helping to decolonize the classroom while creating visibility for Native students at UW Tacoma.

Main Content

Multiple Versions of the Same Person

UW Tacoma faculty member Michelle Montgomery explores identity in her book about mixed-race American Indians.