The Accumulated Wisdom of Tom Diehm

After spending 24 years at UW Tacoma connecting social work students to agencies, Tom Diehm knows something about community building and the costs of field experience.

The year is 1983 and Tom Diehm is in a rut. The then-twenty something is working as a medical records transcriptionist for a private psychiatric hospital in Colorado Springs, Colo. By this time Diehm has already completed a bachelor’s degree in history as well as a master’s in student personnel services. The transcription job is a means to an end. The paycheck allows him to pay the bills, but it’s not fulfilling.

Make a gift in of honor Tom Diehm’s retirementIf Tom’s work and dedication inspires you, consider giving to the UW Tacoma School of Social Work and Criminal Justice Field Education Support Fund. This fund supports field education experiences of UW Tacoma Social Work students.

|

The hospital posts a position in its admissions office. Diehm applies and is eventually hired. “It was still just a job,” he said. Diehm works the evening shift. Medical transcription is a largely solitary world where the work is straight-forward and fairly predictable. Diehm’s new role is the exact opposite. He is the person charged with welcoming new patients to the hospital. “I just became fascinated watching what was going on, the work that was being done with folks whose lives had just completely come apart,” he said.

The facility is staffed by doctors, nurses, counselors and other professionals, but Diehm is drawn to the social workers. “The work they did really interested me,” he said. Diehm decided to return to school. He enrolled at the University of Southern Colorado (now Colorado State University Pueblo) to pursue a bachelor of social work. He went on to complete a master of social work at the University of Denver as well as a Ph.D. in social work and social research from Portland State University.

Diehm eventually left his position at the psychiatric hospital to work in the crisis center at a community mental health agency. “I did that for about five years and then became the clinical director for residential services for adults with severe and persistent chronic mental illness,” he said. “It was really very rewarding. When I was at the crisis center, I saw people at their absolute worst, and, in residential services, I would see many of those same people at their best when they were really functioning well.”

* * *

For some, knowledge is power. There’s a certain personality type that uses what they know to bolster self and no one else. Thomas Diehm is not that person. He is generous with his time and his accumulated wisdom. Diehm’s openness and gentle candor are well-suited for the field of social work. As it turns out, these traits are also a good match for higher education.

Diehm started teaching part-time at the University of Southern Colorado in 1996. There he met Marcie Lazzari. “She was my director at USC,” said Diehm. Lazzari left the school in 1998 to help start the social welfare program at UW Tacoma. “They [UW Tacoma] needed to hire a field director,” said Diehm. “Marcie sent me the announcement and asked if I was interested.”

“The human service providers in Tacoma and the South Sound are incredibly committed to the work they do, and receive almost no credit for it at all."

—— Dr. Tom Diehm

It’s worth noting that the UW School of Social Work is tied for number three in the nation in the most recent U.S. News & World Report graduate school rankings. Undergraduate and graduate degrees in social work offered by the School of Social Work & Criminal Justice at UW Tacoma are accredited as part of the UW School of Social Work. This information is important considering the program had just admitted its first 23 students the quarter that Diehm came to the Tacoma campus.

A small but dedicated group of staff and faculty, including Lazzari and Diehm helped build the program at UW Tacoma into one that is respected nationally. Diehm did his part by cultivating relationships both on campus and in the community. As field director, he helped students gain experience through their practicum placements. “There was no field program when I got here,” he said. “All we had was a list of agencies that had expressed interest in working with us when the program got up and running.”

Contrast the situation back in 1998 to the current one. “Now we have access to something like 600 or 700 field agencies around the region and from that we have a regular group of about one hundred agencies that we use for both our bachelor’s and master’s level students,” said Diehm.

This list is impressive and speaks to both need as well as reputation. “These agencies talk to other agencies and say something like, ‘We just got this great student from UW Tacoma, and you might want to talk to them about becoming a field agency,’” said Diehm.

Graduates of the program are sought after, especially locally. “There are a couple of agencies in town where our alumni pretty much completely populate their social service departments,” said Diehm. It’s not uncommon for students to be hired by an agency while they are still doing their practicum hours. “They don’t want to lose them when they graduate,” said Diehm.

Diehm believes the program’s success ultimately comes down to the community that has been developed over the years. “Everything we do is student-centered,” said Diehm. “We’re big enough to be able to access resources and to attract really good faculty, but we’re not so big that students get lost in the shuffle.”

Change, namely the capacity to transform, is a big part of Diehm’s professional philosophy. “For many, many years I taught the very first class a new master’s student would take,” he said. “Once that quarter ended I would see them [the students] again intermittently throughout their program, but I never had them in class again.”

He may not have had them in class again, but Diehm did work with these students as they did their practicum. “To do my final field visit with them just before they’re getting ready to graduate was just this incredibly warm feeling,” he said. “I watched that student grow from a deer in the headlights during their very first class — ‘I don’t think I can do this’ — to being really confident and ready to head out into the world of human services, as challenging as it is, and give it their best shot.”

Change is easy to type and hard to do, but it can be done. “As a social worker, something you learn fairly quickly is to redefine your definition of progress,” said Diehm. “It’s about being happy with small, incremental change. I really believe that there is no client that can’t be helped.”

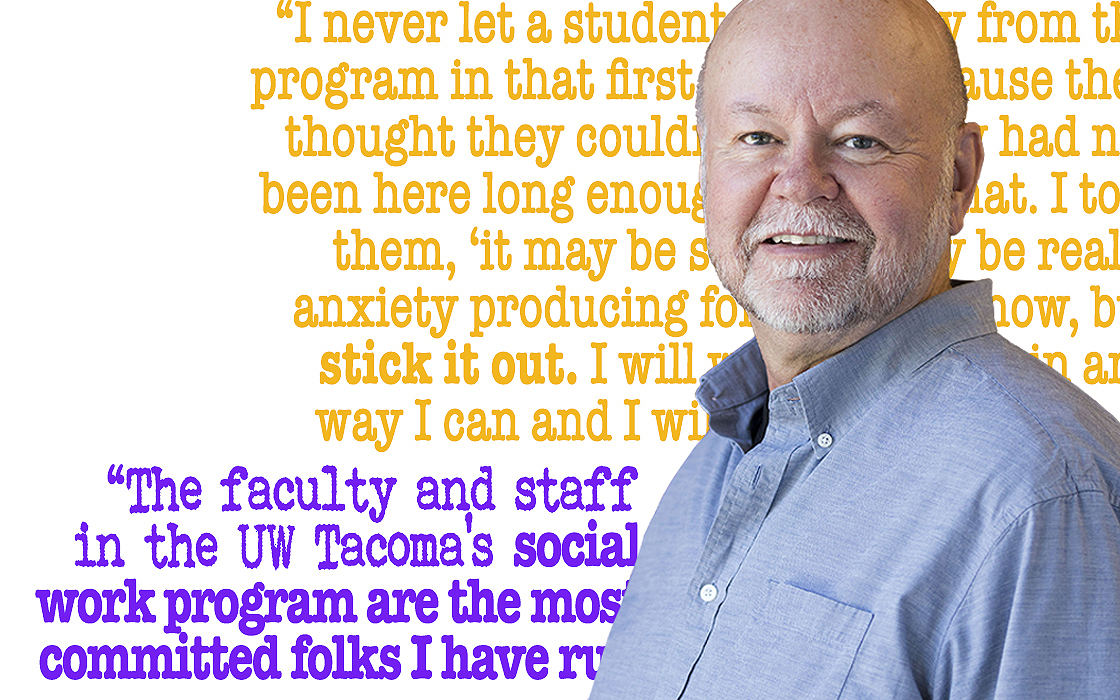

This philosophy can almost be copied and pasted in its entirety to a paragraph about what it means to be an educator. “I had students in my office who really questioned whether they could do this work,” said Diehm. “I never let a student walk away from the program in that first quarter because they thought they couldn’t do it. They had not been here long enough to know that. I told them, ‘It may be scary, it may be really anxiety-producing for you right now, but stick it out. I will work with you in any way I can and I will see you graduate at the end.’”

* * *

It seems fitting that someone so comfortable with change decided to make one himself. Diehm retired in June and now holds the title of Teaching Professor Emeritus. He plans to spend his free time reading and serving as Board President at the Tacoma Community House (TCH). “I’m in my eighth year with the Tacoma Community House and I’ll do one more year before my time on the board ends,” he said. “I really enjoy board work and plan to continue once my time at TCH ends.”

Diehm may be retired but he’ll still remain very much involved with one aspect of UW Tacoma’s social welfare program. Diehm and his husband Tom Davis are working to establish an endowment that will help students pay for costs associated with field experience. Davis worked for years as a researcher at the UW Center for AIDS Research at Harborview Hospital. “There are a fair number of ancillary expenses,” said Diehm. “For instance, if a student does their field work in a school then they’ll have to pay for the cost of a fingerprint background check. If a student goes to a domestic violence agency then there is a thirty-hour training they have to attend before they can even start and the cost of that training is passed along to the student.”

These costs add up. “Almost all of the students in our master’s program are working full-time while getting their degree and doing a practicum placement,” said Diehm. “Many have kids but all are insanely busy and these extra fees can end up costing them three-hundred to four-hundred dollars.”

Besides helping reimburse students, Diehm also wants to use endowment funds to provide training to new field agencies and new field instructors who work with UW Tacoma social welfare students. “We’re trying to even the playing field for those instructors,” he said. “The people out in the community who do this, both the agencies and the field instructors, do it for free.”

For some, knowledge is power. Information is to be collected and guarded. For some, knowledge is transformative. Information is to be accessed, barriers to entry removed. This is perhaps Tom Diehm’s central belief, one that he lived for 23 years at UW Tacoma and one this endowment will continue to nurture.